Melba Escobar: "Those who remain are always talking about those who left, as if they had died"

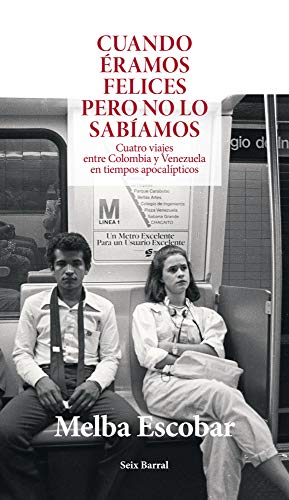

The daily life of Venezuelans is the focus of the book 'Cuando éramos felices pero no lo sabíamos,' the latest work by Colombian journalist Melba Escobar

Melba Escobar is very clear about who her latest book is dedicated to: her mother. It was while her mother was dying of cancer that this renowned Colombian writer and journalist decided to take a series of trips to Venezuela to tell “the daily life of Venezuelans who have not emigrated anywhere" in a book.

“I wanted to tell what happens in people’s lives when they live in a prolonged state of emergency. What happens when that emergency falls into oblivion, when life goes on, despite everything, and people resign themselves to living it amidst the rubble,” she writes in the first chapter of Cuando éramos felices pero no lo sabíamos (When We Were Happy but We Didn’t Know It).

Narrated in the first person, the book compiles a series of chronicles and interviews conducted by the author during four trips to Venezuela between 2019 and 2020 with the aim of bringing readers closer to the day-to-day life of its citizens and understanding the effects of the state or its absence on daily life.

“It made me very angry to see how in Colombia the right wing invented the threat of 'Castro-Chavismo' to win votes, that permanent use of a human

tragedy by politicians and the media. 'We don’t want to end up like Venezuela,' they repeat without really knowing what we are talking about or what happened,” Escobar explained by video call from her home in Barcelona, where she has been living with her husband and two children for a year.

The move to Barcelona was no coincidence. Her mother, a Spanish national, lived in the Catalan capital until she was in her 20s and Escobar has family there.

“I wanted my children to live a day-to-day life very different from the one we live in Bogotá. I wanted to take them out of such a polarized and divided society, where freedoms are quite restricted,” she justified her decision to emigrate to Spain a year after her mother died.

Unfortunately, her mother passed away between the third and fourth trip and she never got her hands on the book. In exchange, Escobar sneaks her into its pages, sharing with the reader the suffering and sadness she feels being away from her when she is dying, as well as putting to use something very valuable she learned from her — her ability to observe reality from a certain distance.

“My mother never stopped feeling like a foreigner in Colombia and was always comparing Colombian society with Spanish and French society, which were the ones she knew best,” she recalled.

Wanting to understand

Her status as a Colombian allowed her to feel “far enough away and close enough to be intimate with the interviewees,” explained Escobar, who as a child always heard about Venezuela as the “rich neighbor.” Now, the situation is reversed. Colombia, a sister country culturally, is now home to more than 1.5 million Venezuelan migrants who have left their country “because they need medicine, because they are about to give birth in a place without hospital services, because they have lost everything, because they are hungry,” Escobar writes in the book.

But what Escobar is interested in telling in her book is not the story of those who leave, but of those who stay. The “left behind.”

“It is very impressive to see that those who remain are always talking about those who left, as if they had died. It’s a bit like the idea of shared mourning,” she said. In fact, she added, “to me it all seems very painful, because globally [Venezuela] has had much less space than the Syrian conflict, or Ukraine. Before Ukraine, the largest number of refugees in the world came out of Venezuela. But, of course, it’s a southern problem and it’s not going to be on the front page. We lack a less hierarchical conception of the world’s problems.”

RELATED CONTENT

While the world forgets about Venezuelans, Maduro’s regime allows “a number of criminals and drug dealers with money building huge restaurants and hotels that nobody can afford, because they are spent in dollars. They are building a Miami inside Caracas,” Escobar commented sadly.

An emotional book

What happens in Caracas or on the luxurious beaches of Maracaibo — now a place for Venezuelan elites and nothing else — has nothing to do with the reality of the rest of the country.

“The car trips through the interior were the hardest,” Escobar recalls. “We drove on roads where there were piles of garbage because no one has picked up the garbage for years, animals lying dead because no one takes them away, no street lighting because there is no electricity. I felt like I was in an apocalyptic movie,” she added. “That’s what the absence of the state means. Something that doesn’t happen in Caracas, which is where Maduro and the boliburgueses, as they call the “millionaires” of the Bolivarian revolution, are.”

Escobar also acknowledged that her book goes beyond being a journalistic text.

“I openly admit that it is a very emotional book,” she said, giving the example of the pain of her mother’s death. “A human pain that accompanied me on every trip, and that still allowed me to adopt a more intimate point of view when talking to my interviewees.”

It is also a book marked by her identity as a woman journalist.

“I think we have a much easier time accepting our shortcomings and ignorance than men. And this is evident in the narrative,” she said. Escobar emphasizes that her book has been written with humility, “from the perspective of a woman who has felt vulnerable in her own country,” she concluded.

LEAVE A COMMENT: