Jessica Hernández, the Indigenous scientist who dares to criticize Western environmentalism

The Salvadoran professor at the University of Washington recently published 'Fresh Banana Leaves.'

With Zapotec roots from Mexico and Ch'orti' roots from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, Dr. Jessica Hernández can boast of being the first Indigenous professor hired by the University of Washington.

Her role as a professor is to teach an introductory course on climate change, where her goal is to incorporate the science and culture of the Indigenous communities — with whom she lived during her childhood — into the fight for environmental preservation.

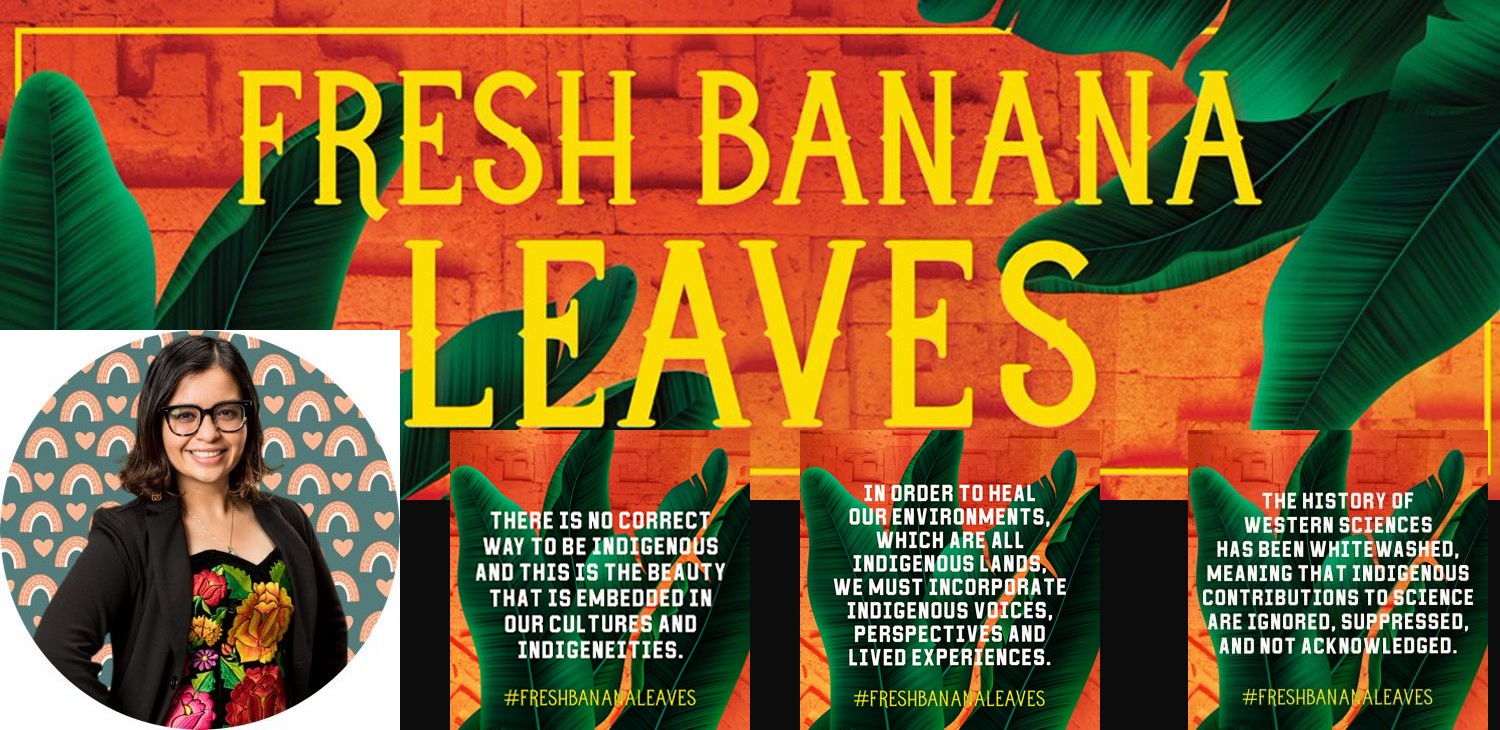

This idea that Indigenous "science" is crucial and much more effective than Western environmentalism in the fight against climate change is also reflected in Hernández's new book, Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes through Indigenous Science, published Jan. 18 by North Atlantic Books.

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/tYpvwoIPOI4.jpg?itok=dOv4r1WF","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tYpvwoIPOI4","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":1},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive, autoplaying)."]}

In Fresh Banana Leaves, Hernández shares her personal story as a Ch'orti' and Binnizá Mayan woman and her life-long experiences as a student of Indigenous science. She weaves together stories of her family and fellow Indigenous organizers, the history of Indigenous and Western environmentalism, and her own experiences as an Indigenous woman navigating Western academia to tell the story of how Indigenous science has survived centuries of colonialism and what we can learn from it now.

The book focuses on the voices of Indigenous peoples in Latin America and highlights resilience in the face of difficult and often unjust circumstances, and imagines a future in which Indigenous peoples have more autonomy over their lands and are treated as prominent leaders in the fight against environmental injustices and climate change.

RELATED CONTENT

Banana trees were introduced to Latin America between the 16th and 19th centuries, grown on plantations under colonialism.

"Under the prism of Western environmentalism, the banana is an invasive species in my ancestral lands," Hernández writes. But she sees it differently.

"Like me and many indigenous peoples in the diaspora, banana trees have also been displaced...forced to adapt to our new environments and form new kinships with our new land," she continues.

Beyond her academic involvement, Hernández is the founder of Piña Soul, SPC, an environmental consulting and crafts business that supports black- and indigenous-led environmental and conservation projects through community grants and micro-grants.

Hernández, a former doctoral student at the UW School of the Environment, where she researched coastal tribes and the effects of climate change on Indigenous communities, believes the scientific community should be more mindful of indigenous communities as they are one of the populations most vulnerable to climate change because they rely heavily on the land where they reside for their livelihoods.

“Scientists continue to make conservation decisions that impact Indigenous people’s rights to traditional foods, medicine, and cultural land use,” Hernández told UW. “In order to change this oppressive top-down approach, Indigenous scientists (like myself) need to utilize their scientific work to advocate for food, climate, and environmental justice.”

Indigenous lands cover about 22% of the world's land area and overlap with areas that are home to 80% of the Earth's biodiversity, according to the Resilience Fund for Climate Justice, as quoted in HipLatina. Indigenous science is based on their connection to the land, so the impact of climate change directly affects not only their food, but their medicine and way of life.

LEAVE A COMMENT: