Latin America, through female eyes

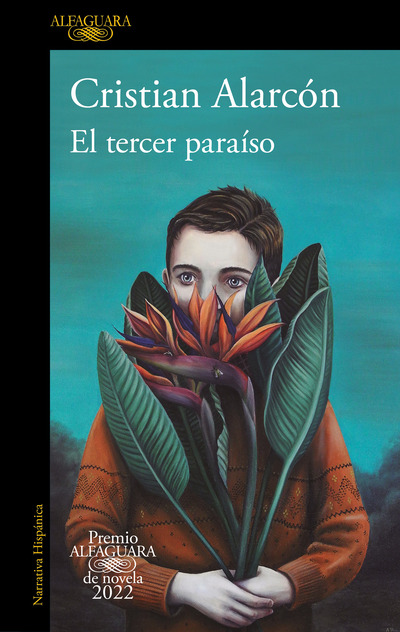

Chilean writer Cristian Alarcón tells 'El Tercer Paraíso' in the first person. It won the Alfaguara Novel Prize this year.

Cristian Alarcón didn’t really want to be a journalist.

“I decided to become one because my parents were not going to pay for my studies to become an actor and because I thought that if I studied literature I would starve to death,” admitted this renowned Chilean writer and journalist based in Argentina, in an interview with AL DIA.

Known for his journalistic chronicles and as founder of Anfibia magazine, Alarcón won this year’s Alfaguara Novel Award with his debut novel, El tercer paraíso, a first-person book that tells of a constant search for happiness around concepts such as family and neo-families, relationships and exile, always linked to the landscape, whether political, emotional or natural.

“I wanted to tell that every life is autofictionalized, that autofiction is not only first person. To build characters based on real events, on our own memory, is to understand that we are not so important. The trap is imposed in the novel, fortunately, beyond all truth. The truth in literature is that time that is ours alone, only and exclusively of the readers,” he explained.

Born in Chile in the midst of the Pinochet dictatorship, his family emigrated to Argentina to escape political repression when he was still a child. This exile condition deeply marked his writing.

“My father was a young man who loved the night, alcohol and gambling. And my mother imagined that exile would transform him, in the background was the dictatorship and the poverty of the socialist workers. For me it wasn’t exile, it was migration, it vindicated me as a migrant: that’s how it is in literature, that’s how it usually is in life,” he said.

The garden as salvation

In addition to narrating the experiences of his family, his childhood and his adult life, Alarcón’s novel displays his interest in gardening:

RELATED CONTENT

“The garden is fundamentally a bid to recognize our impossibility to govern nature absolutely, it is an invitation to humility,” he explains. And he adds: “The garden has been the salvation of women ravaged by male violence, a promise of beauty in the midst of the cruel city. Something that has been related to the third age, with the rest of the retired, after the pandemic rejuvenated and became an unexpected space of revolution.”

After 20 years dedicated to journalism, making the leap to fiction and shedding journalistic objectivity was not as difficult as he thought.

“It is a complex process, but at the moment of betting on crossing the border, there are no longer ties or conditioning,” he said. “Fiction literature is coldness, strategy, structure, it owes nothing to reality.”

On several occasions, Alarcón has said that her new novel tries to “tell the history of Latin America from a conscious feminist perspective,” putting women as protagonists.

“The voice of women is the maternal voice, that’s why I did it. The maternal voice is not only that of our mothers, it is a continent drawn, traced, sculpted by their narratives. The fact that machismo and patriarchy have kept them on the margins of the literary canon does not mean that their centrality is not foundational, always promising. The ancestral is feminine, and so is the possible future,” he said.

The novel, for the moment, has not been translated into English, but for the U.S. Latino reader who dares to read El tercer paraíso in Spanish, “perhaps it is the refuge that many hope or desire, perhaps this paradise is so Latino that for those who are most integrated into the North American way of life it is reason enough to run away,” he concluded.

LEAVE A COMMENT: