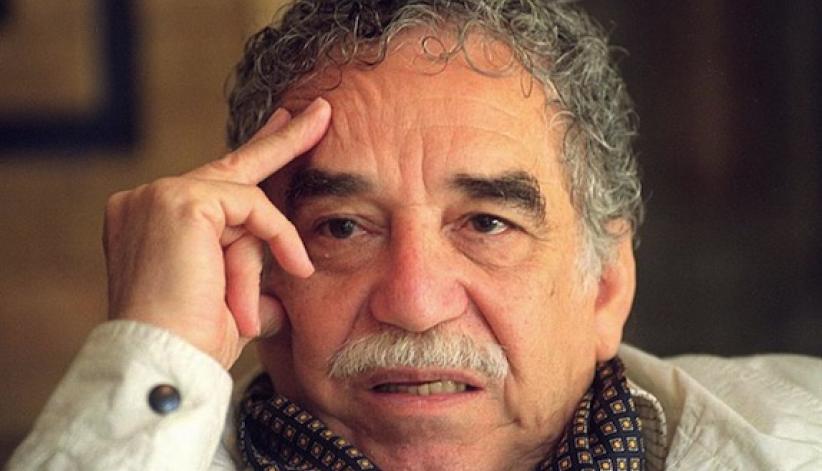

Gabo and Faulkner

Haz clic aquí para leer el artículo en español

From one literary master to another: Admiration and praise

At different points in his life, Gabriel García Márquez expressed admiration for writers as diverse as Franz Kafka and Virginia Woolf. But no admiration was more ardent, or more frequently expressed, than for the work of the quintessentially Southern U.S. writer William Faulkner.

As a young journalist, García Márquez wrote opinion pieces — often touching on literature and film — in a column titled "The giraffe," which appeared in El Heraldo newspaper in Barranquilla, Colombia in the 1950s. Those columns mention Faulkner. A lot.

In April of 1950, while still waiting for Faulkner to receive Nobel Prize for Literature (although Faulkner won the 1949 prize, he did not receive the award until 1950), García Márquez wrote: "in the United States there is a gentleman named William Faulkner, who is something like the most extraordinary novelist of the modern world. Nothing more and nothing less."

And after Faulkner won García Márquez wrote another column (in November of 1950) where he lamented the quality of previous Nobel literature winners by comparison: "Exceptionally, the Nobel Prize for Literature was award to an author of countless merits, within which not the least important is that he is currently the world's greatest novelist and one of the most interesting of all times. And although he is the exception in the master list of Nobel Prizes, this selection indicates that the famous award is trying to transit much higher ground than has been its natural course until now."

In his "The Giraffe" column of February of 1951 he listed Faulkner as one his favorite authors, and said it was his "maximum" aspiration" to write like him.

"It took the French and the Central and South Americans to convince his native land of Faulkner's genius," said Allan Gurganus, novelist, short story writer, and essayist whose work (which includes the novel Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All and the recent collection of novellas, Local Souls) is often influenced by and set in his native North Carolina.

"The great García Márquez took the measurements of Faulkner's farms and villages then mapped and mythicized his own. Erotic obsession, incestuous connection, the erotic recognition of animals as cousins, the greatness of Faulkner is echoed and enlarged by Márquez's humor and wisdom," he said. "And so the dance in the blood of one genius calls out from generation to generation, continent to continent."

Gurganus adds that he is "grieving for Márquez" as if it were a death in the family.

Bengali-American novelist and short story writer Jhumpa Lahiri, whose debut collection of short stories Interpreter of Maladies won the Pulitzer Prize and who recently released her second novel, The Lowland, sees the connection between García Márquez and Faulkner in the characters and worlds created.

"(Márquez's) respect for his characters, their suffering and their dignity, is profound," Lahiri said. "Like Faulkner, like Hardy, his invented world was, in the end, both everywhere and nowhere, both bound by its particulars and universal. He could describe anything and make it seem essential, urgent, real."

García Márquez's success, and the success of the Latin American Boom authors that followed him, produced something of a backlash in Latin America. For Argentine author Diego Fonseca: "From Cortázar to García Márquez, from a childish existentialism to sticky Baroque, everything was infuriating to me. Denying its existence was necessary in order to find a place in the sun."

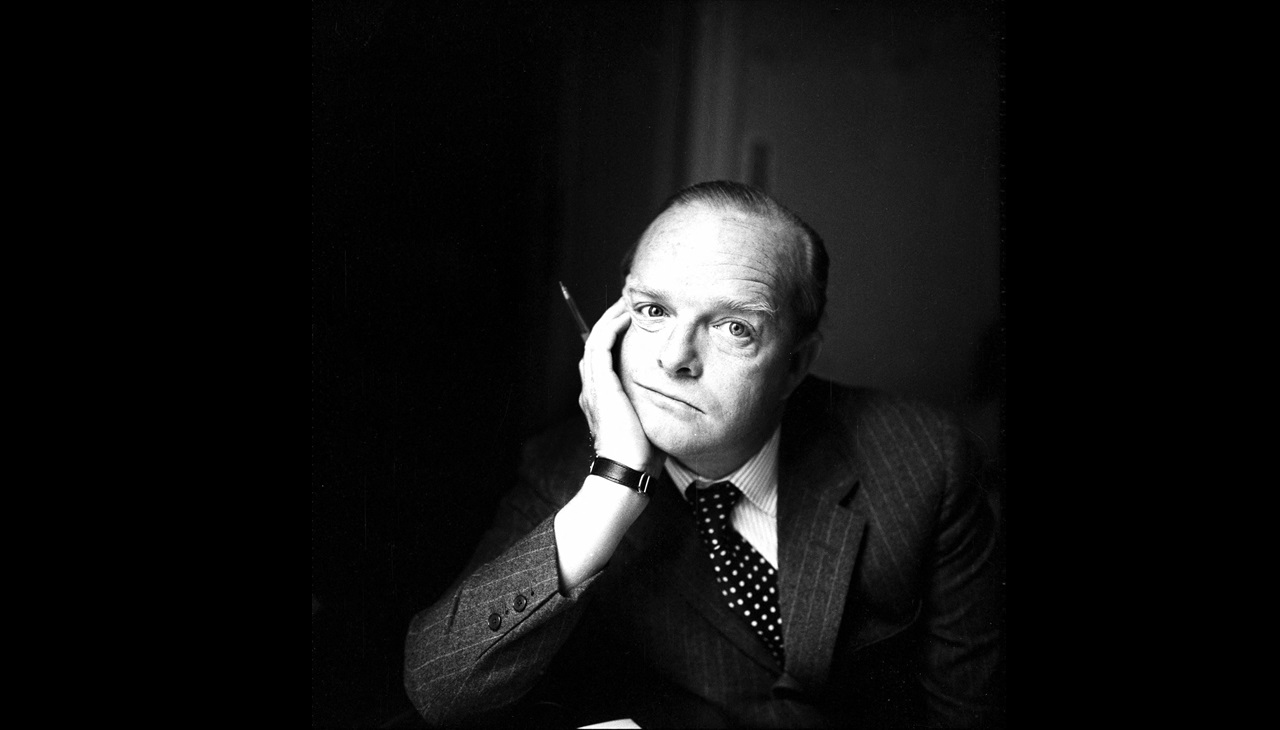

In the United States the linguistic extravagance of some of the "Boom" writers started to seem a parody of itself and many of those who wrote in that ornate style found they were no longer critical darlings. But, say those who have closely worked with the Colombian Nobel winner's writing — his translator Edith Grossman, and Columbia University professor Alfred MacAdam — García Márquez's admiration and affinity for Faulkner never manifested in a baroque stylistic anyway.

"Other Boom writers, (Mario) Vargas Llosa, (Julio) Cortazar, Carlos Fuentes, use rather baroque sentences," Grossman said. "García Márquez didn't. He was more Hemingway than Faulkner in the sense that he used simple, straightforward language."

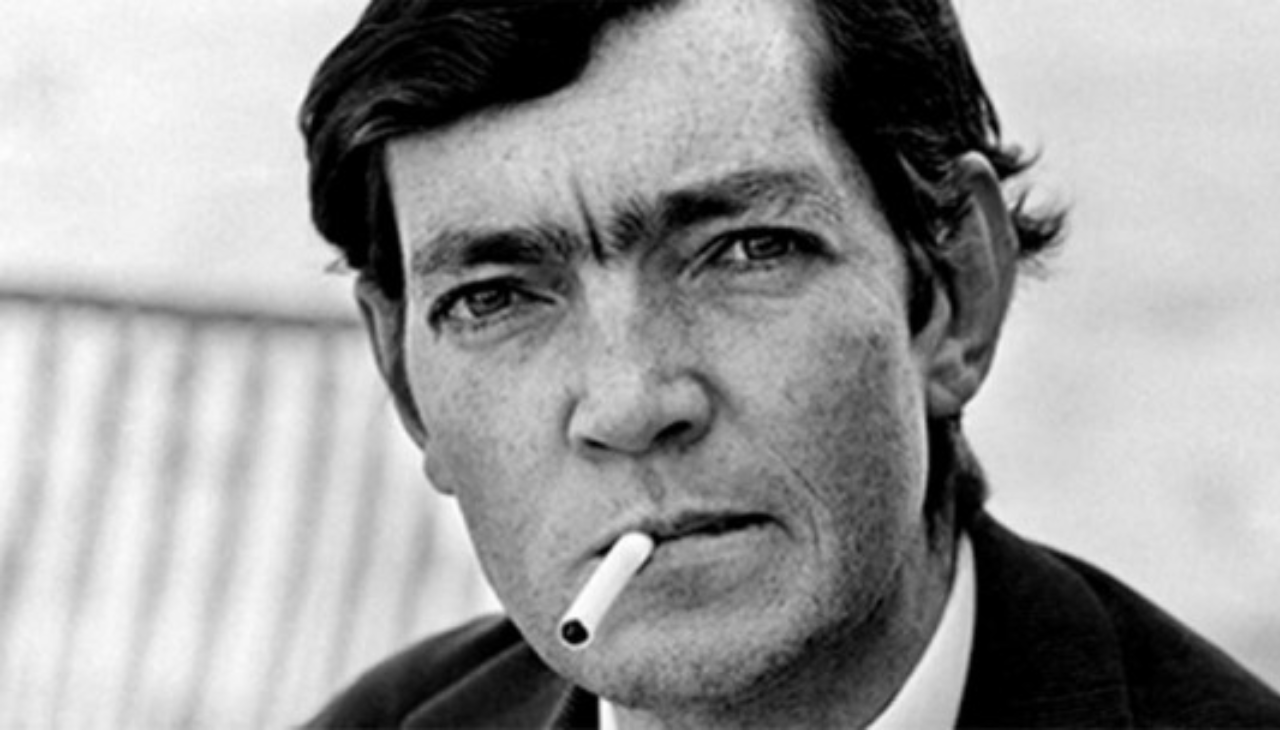

As for MacAdam, he tells the story that when García Márquez first arrived in exile to Mexico, his friend Álvaro Mutis, a Colombian novelist and poet with the more typically Latin American rambling style, handed him a copy of Pedro Páramo, by the famously spare and concise Mexican writer Juan Rulfo.

"Welcome to Mexico," Mutis allegedly said. "Here is a book you have to read."

DEJE UN COMENTARIO:

¡Únete a la discusión! Deja un comentario.