“GABO” in "Subjuntivo" -10 Years Later

On the 10th anniversary of the passing of Gabriel Garcia Márquez, better known as “Gabo”, hundreds, if not thousands of pages, are being written this week and probably

MORE IN THIS SECTION

Listen this article

On the 10th anniversary of the passing of Gabriel Garcia Márquez, better known as “Gabo”, hundreds, if not thousands of pages, are being written this week and probably for another 30 days when this “Macondiana Rain” will subside again.

Paying homage to the man who —as he himself put it once— gave his country of birth more prestige than all the Presidents of that nation combined, to the patient AL DÍA readers we want say this weekend:

If you give us a few minutes of your time to read —patient reader of AL DÍA— ro peruse over these lines on “El Maestro”, we will be very much obliged.

When García Márquez lived in Paris, France, in his early 30’s without a cent to buy a piece of bread, or a letter from his friends or family to read, or a paycheck from his newspaper "El Espectador" (shutdown in Bogotá, Colombia, at the time by the military government that have come to power) he found the time and solace to craft what is considered his most classical piece of prose he wrote, that came to be known as "No One Writes to The Colonel", a short story, a novella, of one the first characters of his mythical town of “Macondo”, the imaginary town where he built his fictional universe.

His Paris years were eugolized and mistify by friends, exiled like him in France, and official biographers from England to Spain— the closest to him Mr. Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, who wrote "El Olor de la Guayaba", using one of the expressions coined by the most universal of the writers born in Colombia so far.

His elaborate craft writing in Spanish not only re-made how things were called in newsrooms in Colombia, as well as the rest of Latin America, but how the reality from the Southern part of the Hemisphere in the Américas was perceived to be.

"Lo Real Maravilloso" (the assumption that the magical and the real are blurred) was adopted as the headline for the new perception of Latin America, not only in the Spanish-speaking part of the world, but also in the more global English-Language from America to the North, and also across the world.

His Mancondiano language so recognizable flowing from his pen eventually became the window through which people "saw" the larger part of the continent, from Mexico to Patagonia.

Journalists and writers in general from the new generations "sounded" definitely "garciamarquianos" for decades.

Such was the powerful influence of García Márquez’s prose over his millions of readers, and thousands upon thousands of imitators— some successful, so many others not.

On this first decade of his departure, one can't avoid but to think again of "El Maestro"— nicknamed "Gabo" by his close friends and family and "Gabito" (little Gabo) for those even closer.

Like his wife, Mercedes Barcha de García Márquez, the mother of his two sons he remained married to until his death— also named "La Gaba" in reviews in all the modern languages of the world in which the work of García Márquez was translated.

To think not only of his many virtues, but also of his flaws as an artist of the written word, or a as a person —like every one of his fellow writers, or plain human beings also may have— is inevitable this week.

His ashes are now scattered:

Half in Mexico City, Half in his Cartagena, Colombia, where a home he always dreamt of living in (overseeing the Caribbean Sea over the City’s 500-year-old wall) is still standing and soon into the future will be a Museum in his honor.

His unedited notes, papers and utensils from his wordsmith desk were sold to the University of Texas (UT) in Austin, where people can now look over this trivia of his life chasing even more clues on what Gabriel García Marquez was, or could have been.

His answer to a TV interviewer from Spain at age 67, when she asked her in Cartagena, what he thought about the possibility of his own death, was disarming:

Not to say "magistral".

"Death is a trap. Death is a Betrayal...

“...Something they throw at you (at us) suddenly with no warnings…

RELATED CONTENT

“..For me it is extremely serious that this (life) ends all of a sudden…”

When he is asked by this same inquistive female journalist what he would like it see through “a little hole at the door, without anybody watching him,” he goes into a pause, before given the reporter what she wanted:

“To be able ‘to see’ life from death…”

Gabriel Garcia Márquez –who knows— may be watching us (panegiristas, or envidiosos) from death through “that little hole at the door”, watching those who considered themselves to be alive this weekend.

Sometimes “alive among ‘the death’,” as Joan Manuel Serrat signs in his popular Spanish-language song.

"In other words, the Spanish-Language of the Nobel from Latin América, carried that weird angle people in Madrid called "Tiempo Subjuntivo"

(Not existent in the English-Language, according to puritanical lexicographers of the bountiful language from Castilla, Spain).

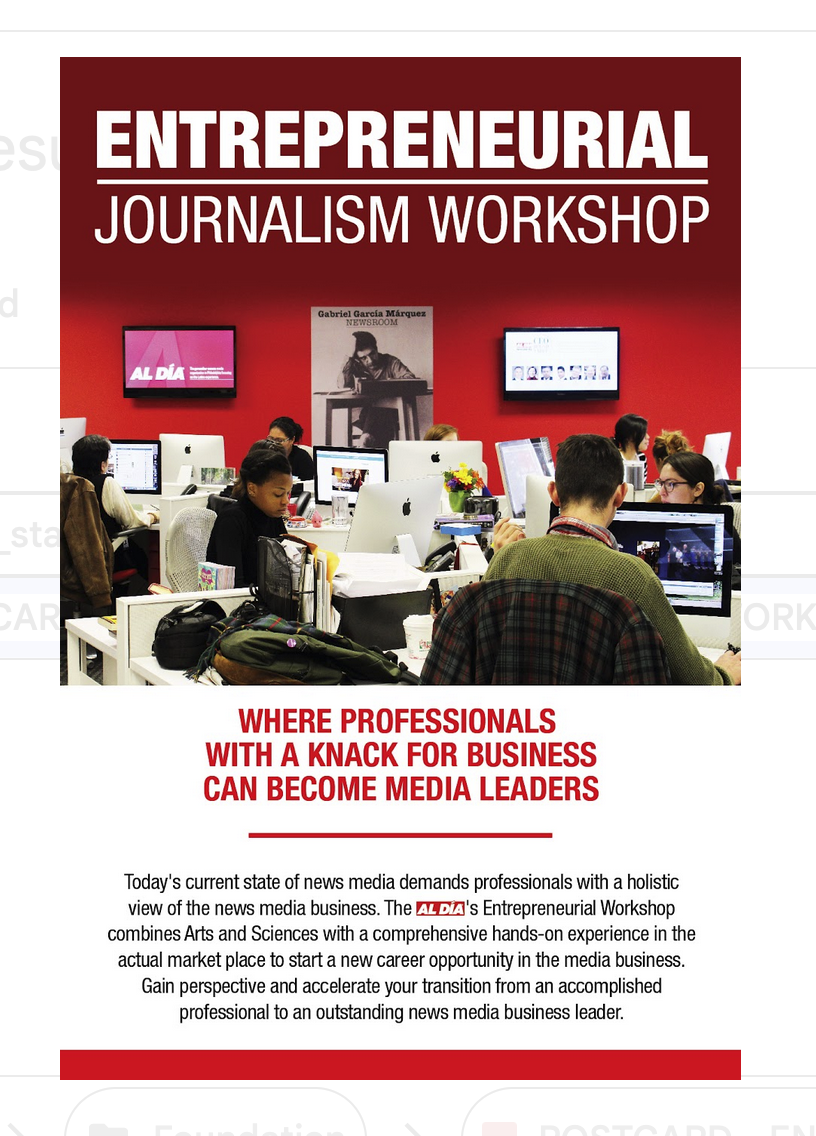

The photo and the name of “El Maestro” presides over the AL DIA Educational Media Foundation Newsroom in Philsdelphia, where dozens of Bilingual Content

Producers have been trained. (AL DÍA Photo Archive)

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.