An American saint of Latino descent: Father Félix Varela

MORE IN THIS SECTION

Although his sainthood is yet to be declared by the Catholic Church, miracles abound in the life of Father Félix Varela, the Latino champion of the Irish immigrants in 19th century America, when they suffered, they fought and, eventually, they prevailed. American society made a space for them, as Latinos are hoping today to carve theirs.

The announcement of the sanctification of Mother Teresa, scheduled to take place in Rome on Sept. 4, 2016, reminded me of another virtuous member of the Catholic clergy who, in no different manner than Mother Teresa did in the 20th century, championed the poor and the persecuted, right here in the United States, 150 years earlier.

His name is Padre Felix Varela y Morales, better known as Father Varela to thousands of immigrants who came to America in the first half of the 19th century, when another wave of immigration was washing over our shores. And, not much different from today, that wave of immigrants stirred controversy in the American society, inevitably clashed with “the natives,” but, in the end, enriched the cultural, economic and political tapestry of America, richer and stronger with their unique contributions celebrated recently on St. Patrick’s Day.

Few know that Father Varela started his American journey right here in Philadelphia, in 1824.

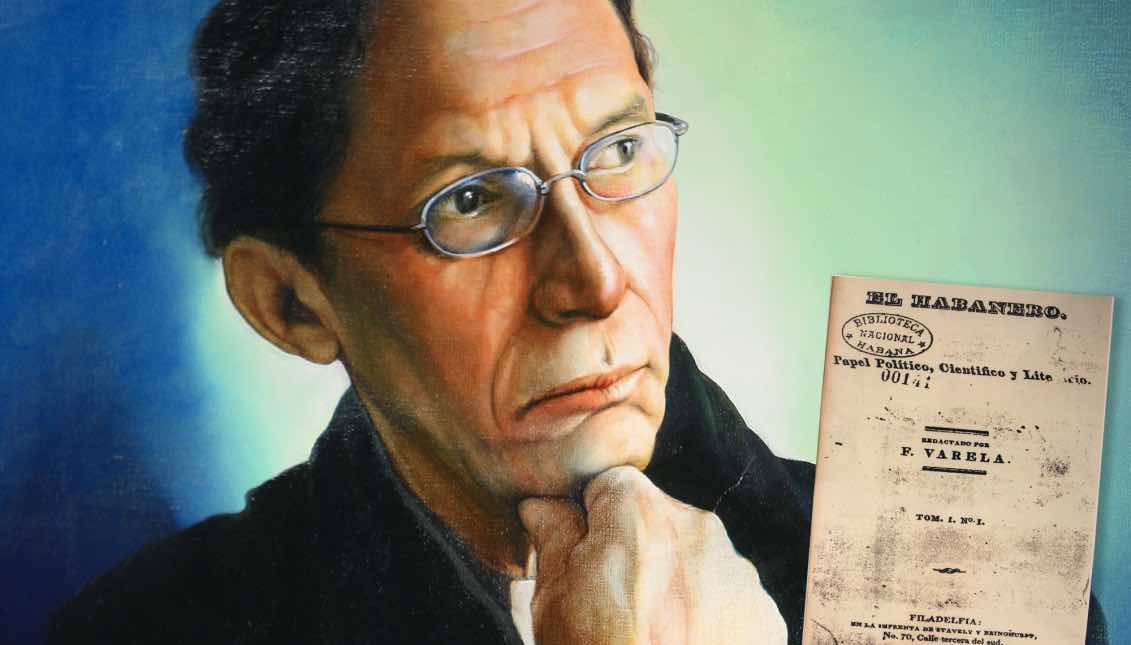

Few know that Father Varela started his American journey right here in Philadelphia, in 1824, when he came to our city that year in search for a printer to publish a little journal with a huge vision he called “El Habanero” (The Man from Havana) in whose pages the island of Cuba — then still a colony of a crumbling Spanish empire — was first imagined as an independent nation, free of colonial power and the shame of slavery.

Varela is revered today by Cubans in the island of Cuba, although he spent most of his life on U.S. soil, where today he is completely anonymous.

He is was called by José Martí "the first Cuban Saint" and he is widely described in the island as “the man who taught us how to think,” because of his philosophical and political thinking about the destiny of his homeland.

He developed his thinking first here in Philadelphia, where he came to publish the first few issues of “El Habanero,” the first Spanish-language publications ever written, printed and published in the United States.

But his greatest achievement in life was not this advocacy for the independence of his homeland, written out in that journalistic enterprise he launched in Old City Philadelphia, but what he did in the following 30 years in New York City, where he moved to lead a life of charity in defense of the poorest of the poor, the undereducated immigrants coming to America in the first half of the 19th century, mostly from an island called Ireland.

Not from the island of Puerto Rico, not from the island of Cuba, not from Mexico, where the 19th century relative prosperity made emigration unnecessary.

St. Patrick’s Day, the big celebration of Irish pride in America, should remember Varela, another yet-to-be-saint, defender of the oppressed, like St. Patrick himself.

St. Patrick’s Day, the big celebration of Irish pride in America, should remember Varela, another yet-to-be-saint that, like St. Patrick, became the champion of the same oppressed people, only this time in America, fleeing what is known as “The Great Famine.”

Before the majestic St. Patrick Cathedral was established on 5th Avenue in New York City as the spiritual center of the emerging Irish American community in the 20th century, Father Varela pioneered a smaller shelter for them, where the widows, orphans and the unemployed men found shelter.

In lower Manhattan, not far from where the ships coming from Europe docked, Father Varela established the small “Church of the Transfiguration,” with meager means but immense heart, to perform countless and unknown miracles for the hungry and poor escaping extreme poverty in Ireland.

One day the Vatican, now presided by the first Latin American Pope in the history of the Church, will do justice and will fully recognize this early American of Latino descent who left his mark in 19th century America.

“No single Latino left a greater imprint on 19th century American culture than Varela,” writes former Philadelphia Daily News writer and New York Daily News columnist, Juan Gonzalez in his book “Harvest of Empire.”

Pope Benedict XVI in 2012 declared Varela “venerable” of the Church, the stage prior to beatification, before canonization, which are the three-step process under which Mother Teresa was granted sainthood status, completing her canonization on fast-track mode only 19 years after her death.

All of us were secretly hoping Pope Francisco would make the announcement of Varela’s beatification, and eventual canonization, when he spoke at Independence Mall, in Philadelphia, a few blocks from where “El Habanero” was born in 1824.

Padre Varela was interred for 163 years in St. Augustine, Fla., where he died in 1853, and his remains were transferred to Havana decades later, laid finally to rest in the University of Havana’s Aula Magna. That is where Saint Juan Paul II paid respect to him when he visited, back in the 90s, and Pope Benedict XVI acknowledged him when he decided to declare him "venerable" during his own his own visit to Cuba in 2012.

Popular culture in Cuba has already declared him a saint, after José Martí called him so, and the few people who know him in the United States don’t doubt the caliber of his spiritual life and world accomplishments.

All of us were secretly hoping Pope Francisco would make the announcement of Varela’s beatification, and eventual canonization, when he spoke at Independence Mall, in Philadelphia, a few blocks from where “El Habanero” was born in 1824.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.