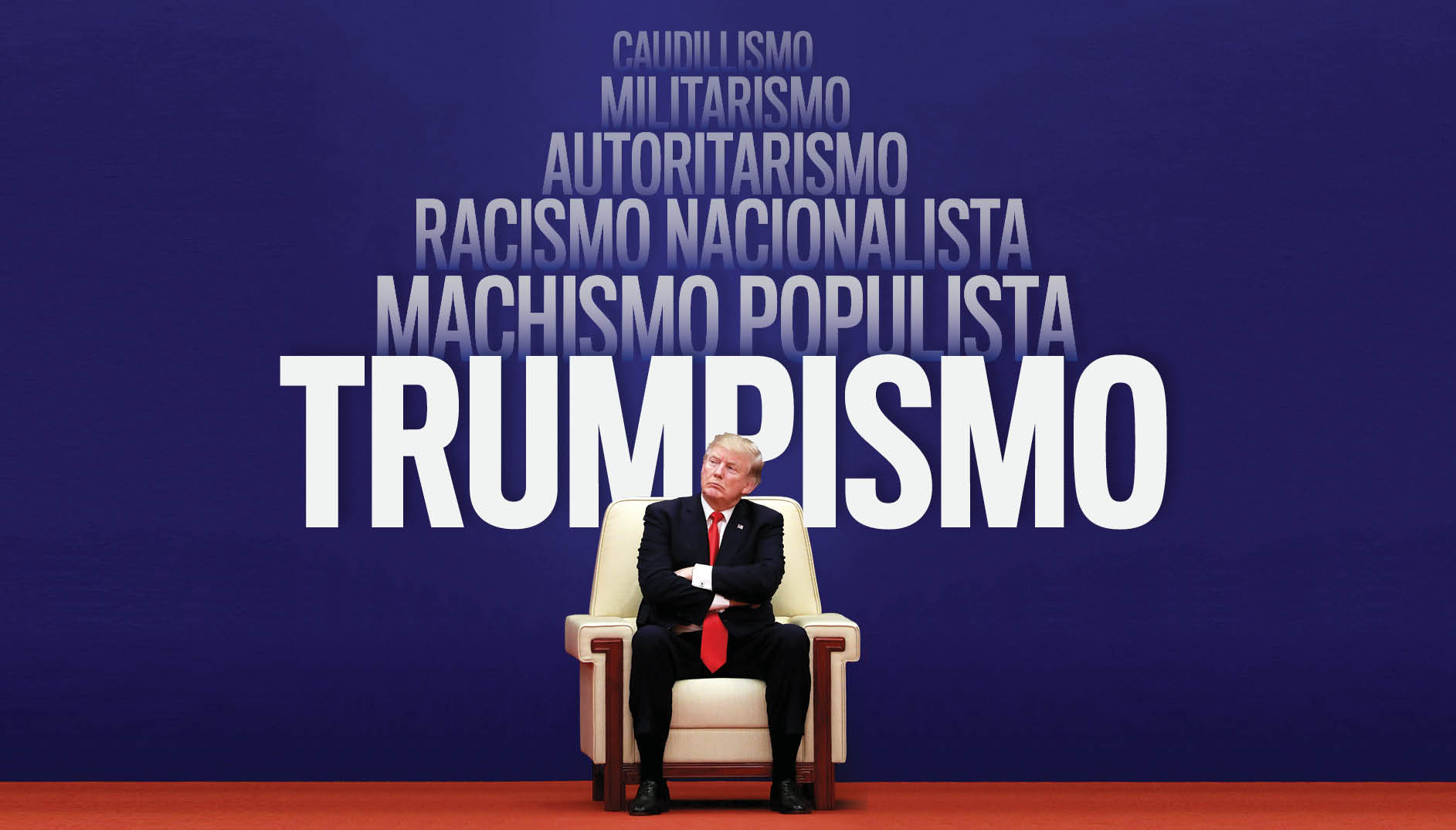

Trumpismo and the Latin-Americanization of U.S. Politics

President Donald Trump is leaving his mark on history with his own unique and, for many, problematic brand of politics.

The buzz in Washington around renewed reports that President Donald Trump may fire Special Counsel Robert Mueller have many thinking of the United States as a Latin American country—of the 1970s.

Trump’s recent firing of former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe further fuels fears and comparisons that cause more than a few Spanish speakers to apply the term “dictador” to the U.S. president. Accompanying these fears are images of angry, U.S.-backed dictators who ruled most of the countries between Argentina and Mexico during the 1960s and 70s.

For many, Trump’s angry tweets trigger reminders of the humiliations and attacks that often preceded the firings — or even killings — perpetrated by classic Latin American caudillos like El Salvador’s General Arturo Armando Molina, who often used Trump-like rhetoric before purging his government. Like Molina, El Salvador’s former president, Trump uses humiliation in complex ways. A single tweet sets the day’s media agenda while simultaneously punishing his adversaries, enforcing loyalty among his allies and, if necessary, preparing purges like the record-breaking number of firings already undertaken. The tweeted dismissal of former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson also bears the marks of Latin American strong men whose state of constant insecurity drove them to act erratically while the rest of their country lived in perpetual confusion and fear.

Increasingly, many in the U.S. find themselves watching the nation’s news under a cloud of confusion, unable to decide whether it’s better to use Spanish or English to describe the United States of the Trump era. The ascendant cloud of the constitutional crisis that looms with the possible firing of Special Counsel Mueller inspires among Latin Americans and others to hear “caudillo,” “dictador” and other terms once common in Latin America where the term “president” appears in U.S. news.

In this sense, Latinos and Latin Americans have a far more developed political vocabulary than the average U.S. citizen, especially when it comes to the authoritarianism and other anti-democratic displays by President Trump. But the rest of the country is quickly catching up, as reflected in Washington Post reporter Ishaan Tharoor’s baptizing Trump as “the U.S.’s first Latin American President.”

News coverage of the McCabe and Tillerson firings, along with many other news stories involving Trump, make two connected and increasingly obvious facts very clear: first, that the United States looks and sounds increasingly like a Latin American dictatorship of the 1960s and 70s, in more ways than one; and secondly, that President Trump is leading the way with his own hybrid of Latin American-style U.S. politics — Trumpismo.

Trumpismo, a term that has crossed the minds of more than a few people throughout the Spanish-speaking world, is both an English and Spanish language term to describe the president’s old-school Latin American approach to governance, a dangerous and uniquely powerful brand of caudillismo—authoritarianism, militarism, nationalist racism and populist machismo—with a new-school ability to set the media agenda of the country and even the planet. The world has never seen a Latin American style of politics like Trumpismo because the U.S. is a global power like no other.

The following analysis shows that Trumpismo is nothing less than an unprecedented threat to democracy, both in this country and worldwide.

Fueling the rapid rise of Trumpismo is the Latin-Americanization of the United States, and not just in terms of its changing demographics and racial composition, but also of its stark— and rapidly growing—division between rich and poor, which ranks very close to the income inequality found in countries like Peru, Honduras and Bolivia, according to the CIA Factbook.

Reports that the United States has moved from being a democracy to being an oligarchy contain echoes of El Salvador, Mexico or Argentina during the 1960s and 70s. To understand Trumpismo, it’s important to understand the things that preceded and led to it, things such as the continued growth and expansion of Pentagon budgets, the continued shrinking of the welfare state or the 3 million deportations of the previous administration—all of which were bipartisan policies, consistent and definitive in the way that they paved the way for Trumpismo. Such a policy agenda is what also paved the way for dictadura, caudillismo and other kinds of governance styles resembling, but not limited to, those of Latin America.

Now, the United States itself is being reconstituted in unprecedented and breathtaking ways that make the rich richer, the poor poorer and the streets more conflicted and, in the view of Trumpismo, in need of increased policing and militarization. Viewed from this perspective, Trump’s highly controversial plan to institute a military parade is as much about laying the foundation for increased militarization within the borders of the United States as it is about communicating U.S. power to the Kim Jong Uns of the world. Again, such tactics are textbook practices to anyone familiar with the governments of Chile’s Augusto Pinochet, Brazil’s dictator Getúlio Vargas and other old-school Latin American politicians.

RELATED CONTENT

Closely related to the militarism that fuels Trumpismo is the nationalism it reinforces. Trump’s call to end NAFTA and other trade agreements actually sounds sensible to those in the U.S.—and Latin America—who have felt the devastation of policies that led to an alarmingly rapid abandonment of industrial, agricultural and other workers, including the white workers whose identity Trumpismo weaponized with the help of Trump’s former chief strategist, Stephen Bannon. Now, Trump’s brand of white nationalism represents the kind of racism and xenophobia that those of us who follow the immigration debate saw in the 90s—but on steroids.

Whether or not the president is ultimately impeached or deposed, the forces that fuel Trumpismo run deep in the history and culture of the United States and, therefore, will not disappear with the political end of Donald Trump. Further complicating the work of defeating these forces is the, for some, uncomfortable fact of U.S. politics that the policies of the Democrats helped create the racial army that opposes them. One need look no further than the ways in which the sharp rise in deportations (almost 3 million) under Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, helped fuel and legitimate drastic immigration policies that, just a decade ago, were the stuff of extremists and fringe groups. Similar enabling of the now mainstreamed extremists scaring the Republican party from below can be seen in the Democrats’ economic policies that continued the hollowing out of the industrial economy that began with President Reagan and sharply increased under Bill Clinton.

As important to Trumpismo and other brands of authoritarian politics is the attempt to draw clear and distinct physical and racial borders, something many Latinos in the U.S. understand as well as anyone. Trump launched his campaign by drawing such lines in the political imagination, saying of Mexicans, by far the largest Latino group, “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” The fact that Trump kicked off his campaign this way did not come as a surprise to a community that has followed U.S. immigration politics since California Governor Pete Wilson launched his own bid for the presidency by attacking Latinos and other immigrants from a podium on Ellis Island in 1995.

The fact that Trumpismo has as one of its centerpieces the idea that construction of even more border walls makes zero political sense not only to Mexicans, who have had to contend with the politics of borders for decades, but also to Dominicans and Haitians, whose countries’ histories were shaped, in no small part, by the immigration and genocidal policies of dictator Rafael Trujillo. Trujillo ushered in the modern Dominican Republic in 1936 by slaughtering tens of thousands of Haitians near the border shared by both countries—all in the name of “whitening” the Dominican Republic.

Adding irony to the tragedy of Haiti and the Dominican Republic is the fact that Trujillo himself was of Afro-Haitian descent. In their fight against Trumpismo, some journalists and scholars are beginning to use “resistance genealogy” to expose the immigration history of those shaping Trump’s racial and physical wall-building policies.

Trumpismo has also given rise to levels of activism in the United States resembling those of the Latin American social movements that toppled the U.S.-backed dictatorships. These social movements have included and will continue to include Latinas like Emma Gonzalez, the Florida high school student whose advocacy has already toppled a Trumpismo politician from Maine who called her a “skinhead lesbian.”

Trumpismo has ignited social activism not seen in the U.S. since the days when fascism first reared its ugly head in the nation and around the world. Viewed through the lens of history, Trump himself is but the figurehead of the powerful institutional and social forces that both helped elect him and and continue to sustain his policies. Because of their experiences with authoritarian politics, increasing numbers of U.S. Latinos and Latin Americans are beginning to manifest the enormous potential many have long predicted the “sleeping giant” possesses, a potential exhibited in the powerful immigrant rights movement, the labor movement, the #MeToo, and other movements rising in response to the election of Trump.

Whether Trumpismo will be toppled depends less on whether Special Counsel Mueller’s investigation leads to President Trump’s impeachment than on whether the vast and growing forces of anti-Trumpismo unite to become one of the greatest political generations in U.S. history.

LEAVE A COMMENT: