Patria, Fernando Aramburu’s Novel: neither Victims nor Executioners

Fernando Aramburu is a poet, essayist and novelist born in 1959 in San Sebastian, Spain. To date he has published more than twenty works and has received several important prizes, including the Prize of the Royal Academy and the Mario Vargas Llosa NH Prize in 2008 for his collection of short stories, Los peces de la amargura (The Fish of Bitterness). But his biggest critical and editorial success has been due to his latest novel, Patria (Home Country), chosen as the book of the year by ABC Cultural, now on its ninth printing with over 100,000 copies sold.

Fernando Aramburu is a poet, essayist and novelist born in 1959 in San Sebastian, Spain. To date he has published more than twenty works and has received several important prizes, including the Prize of the Royal Academy and the Mario Vargas Llosa NH Prize in 2008 for his collection of short stories, Los peces de la amargura (The Fish of Bitterness). But his biggest critical and editorial success has been due to his latest novel, Patria (Home Country), chosen as the book of the year by ABC Cultural, now on its ninth printing with over 100,000 copies sold.

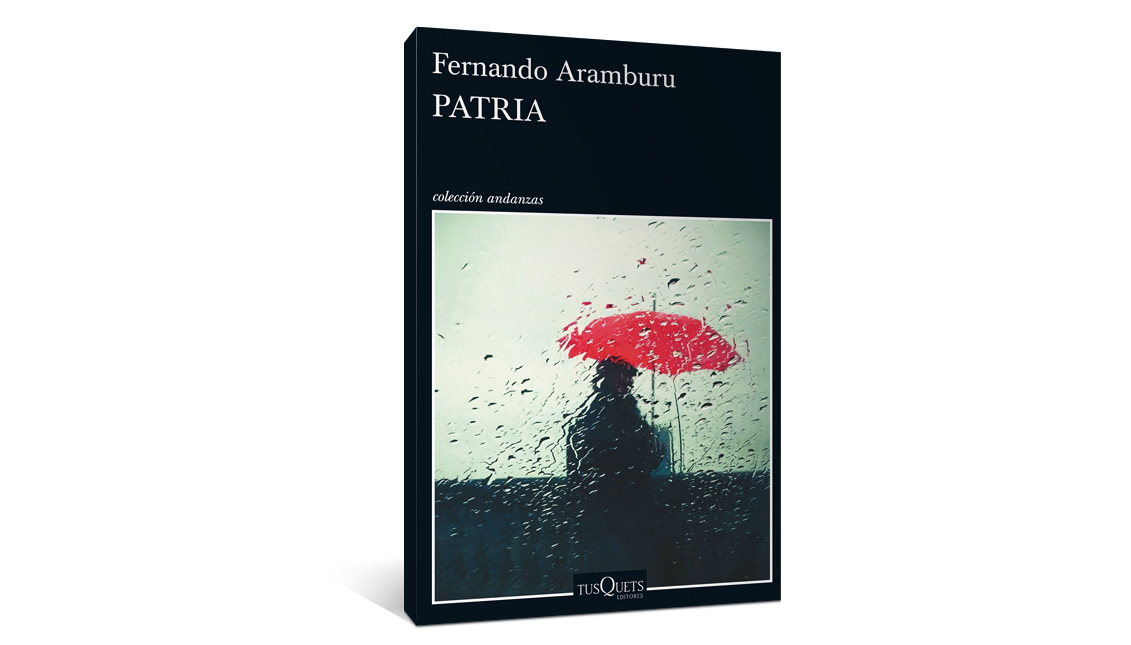

Patria (Barcelona, Tusquets, 2016) is a passionate and impassioned novel about the consequences of ETA on the Basque people, although none of its many characters in its over six-hundred pages, is neither a simple victim nor an executioner. ETA is the Basque terrorist group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque Country and Freedom) that caused over eight hundred deaths from its inception in 1959 to the final cease-fire in 2011, in addition to numerous bombings, kidnappings and other acts of terrorism.

Narrated mostly in third person, with 125 titled chapters, the action is focused on two Basque families during the years of one of the cease-fire truces declared by ETA. Bittori is Txato’s widow whose husband, a company owner, has been murdered because he hasn’t paid the bribe imposed by the terrorist group. In her role of the matriarchal figure, who cannot forget or forget the crime perpetrated against her husband, Bitori seems like a crazed person, but her characterization, as with the other characters, surprises us due to its complexity. Her obsessive daily visits to the cemetery, where she speaks with her dead husband and her return to the town where the assassin’s family lives are dramatic. Bittori’s and Txato’s children are equally complex; Xabier is a doctor, who has apparently overcome the family tragedy, but he hides behind his drinking and is unable to make long-lasting emotional commitments. Nerea, his sister, is even more deeply marked by the situation, and affected by the law of silence, doesn’t attend her father’s funeral for fear to be identified by her acquaintances.

The antagonist family formed by Miren and her husband Joxián, with their three children, is equally well-characterized. Miren runs the household and it is she who stays in touch with Joxe Mari, her terrorist son, incarcerated far from the Basque Country under the Dispersion Law. Arantxa, his sister, is an unforgettable character, touched not only by her family’s plight but left incapacitated by a stroke that leaves her at the mercy of others. Gorka, the other son, is also an interesting character; a writer who succeeds in escaping the terrorist pull, and who shows his love of the Basque Country by studying and learning Euskera, the regional language. He could be an alter-ego of the author, since Aramburu tells us in an interview that “due to certain reasons” he didn’t join the ETA organization; perhaps because he grew up in a city, San Sebastian, instead of a small town, where control over the youth was a lot stronger (el confidencial.com/cultural).

The plot is developed chronologically, but frequent flashbacks dwell in the lives of the protagonists; despite the official peace of the truce by ETA at that time, there is no peace whatsoever in their private lives. The suspense about the exact facts about Txato’s murder, and finding out if Joxe Mari was the one who committed the crime or not, captures the reader’s attention.

This emphasis on the private lives of the people instead of the historical facts can be related to the theory of another Basque writer, Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936). Unamuno defines true “History,” as the day to day life of people or “Intra-historia,” not the official history found in upper case letters in textbooks. As a contrast to Patria and its interest on the quotidian instead of the political, the memoir Secuestrado por ETA (Kidnapped by ETA. Madrid, Ediciones Temas de Hoy, 1991), by another writer, a diplomat and a politician, Javier Rupérez, comes to mind. In this book the emphasis is centered on the negotiations of the political figures of the times, including the President, Adolfo Suárez, all the way to the Pope, John Paul II.

The language in Patria is apparently simple; Aramburu tells that: “I should avoid at all costs that some illiterate person would sound like a philosophy professor” (el confidencial.com/cultural). But its language has some interesting traits. For example, often the slash between words is used to attract the reader’s attention; the narrator tells us about Joxe Mari’s prison stay: “In a fit of rage/hopelessness, of disgust/anguish, he punched the wall” (864). Many words in Euskera are also used, which gives a realist touch to the discourse, there is an extensive glossary at the back of the book. Another remarkable linguistic trait are the sentences cut off by the prepositions: “Nerea spoke at length about her sightseeing adventures (we entered in, went to, walked by)” (205).

Some important themes in the novel are forgetting and forgiving. It seems to be easier to reach the first than the second. Nerea insists in attending some healing encounters in the prison and Bittori writes some very emotional letters to Joxe Mari, hoping that he will ask for forgiveness. It’s worth noting the role of the Catholic Church in that society; the village priest is the spokesperson for the nationalistic and traditional values. The apparent simplicity of the book’s title, Patria or homeland, is precisely a reference to these overpowering, nationalistic tendencies.

In Spain ETA’s has been amply dealt with on the screen; there are over thirty documentaries and full length films about this terrorist group. However, there are very few novels; it’s like the law of silence had reached all the way to literature. Aramburu tells us in an interview: “We novelists have been the last ones arriving, we are the destined ones to leave the everlasting words about what happened in Euskadi all these years” (el confidencial.com/cultural).

LEAVE A COMMENT: