Brazil’s middle class exodus

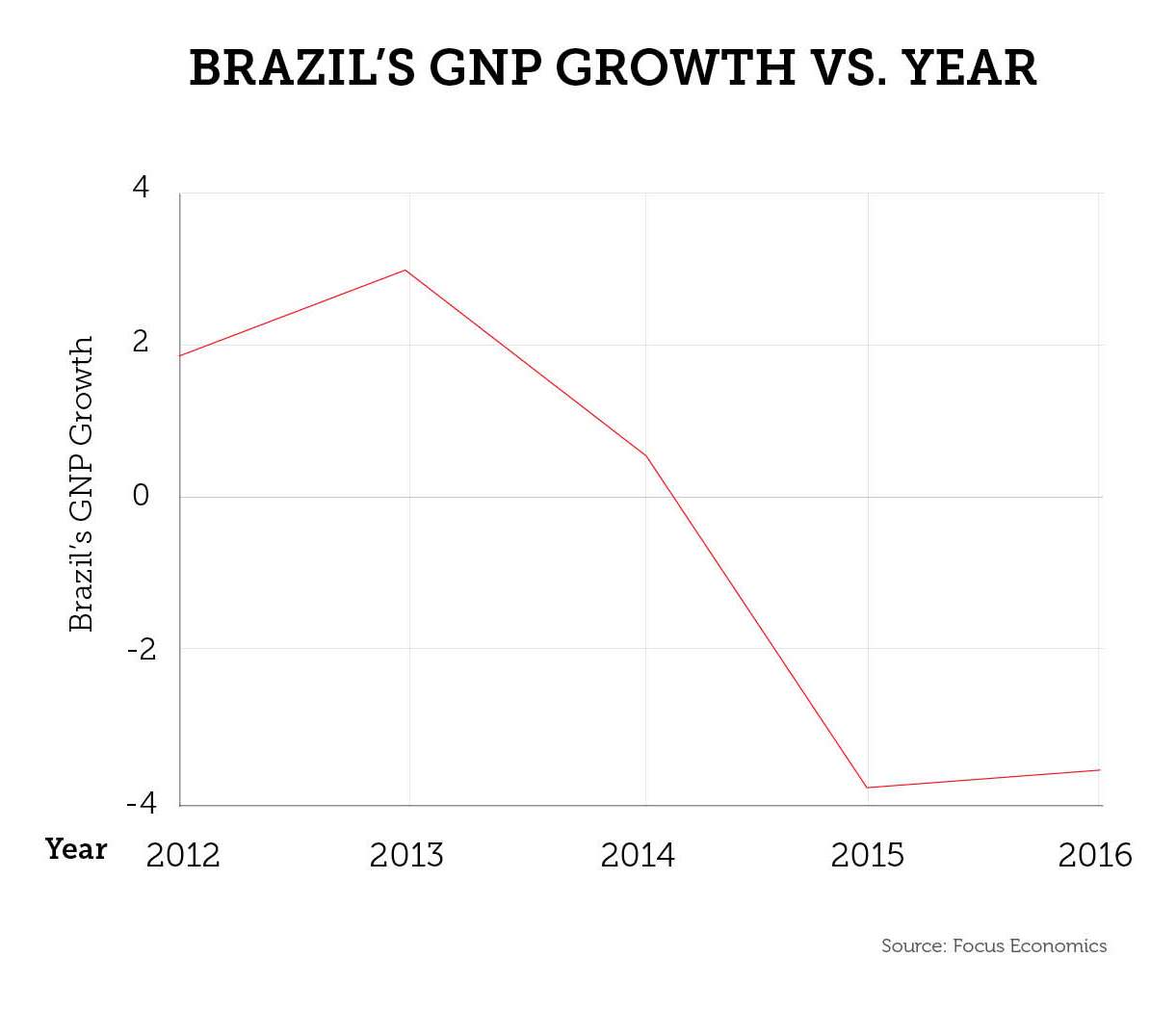

The nation’s severe economic recession and corrupt politicians are two reasons why members of the middle class are fleeing Brazil in droves.

A Brazilian professional found himself at a dead end.

The well-established company that the 45-year-old worked for filed for bankruptcy due to the economic crisis plaguing his home country. As the only source of income for his family, he and his loved ones made an enormous decision — they fled Brazil in search of opportunities in the U.S.

This man, who did not wish to be identified due to visa concerns, made a choice that is not unique. Since the recession hit the country, more and more Brazilians are spending their savings to seek better lives in the U.S.

Along with the deteriorating economy, a large percentage of these migrants point to Brazil’s corrupt political system, and the frustration that comes with it, as a major reason for coming to the U.S.

Some come documented while others do not, but at the end of the day they all face similar challenges during a time period when immigrants are widely perceived as a threat to the American working class.

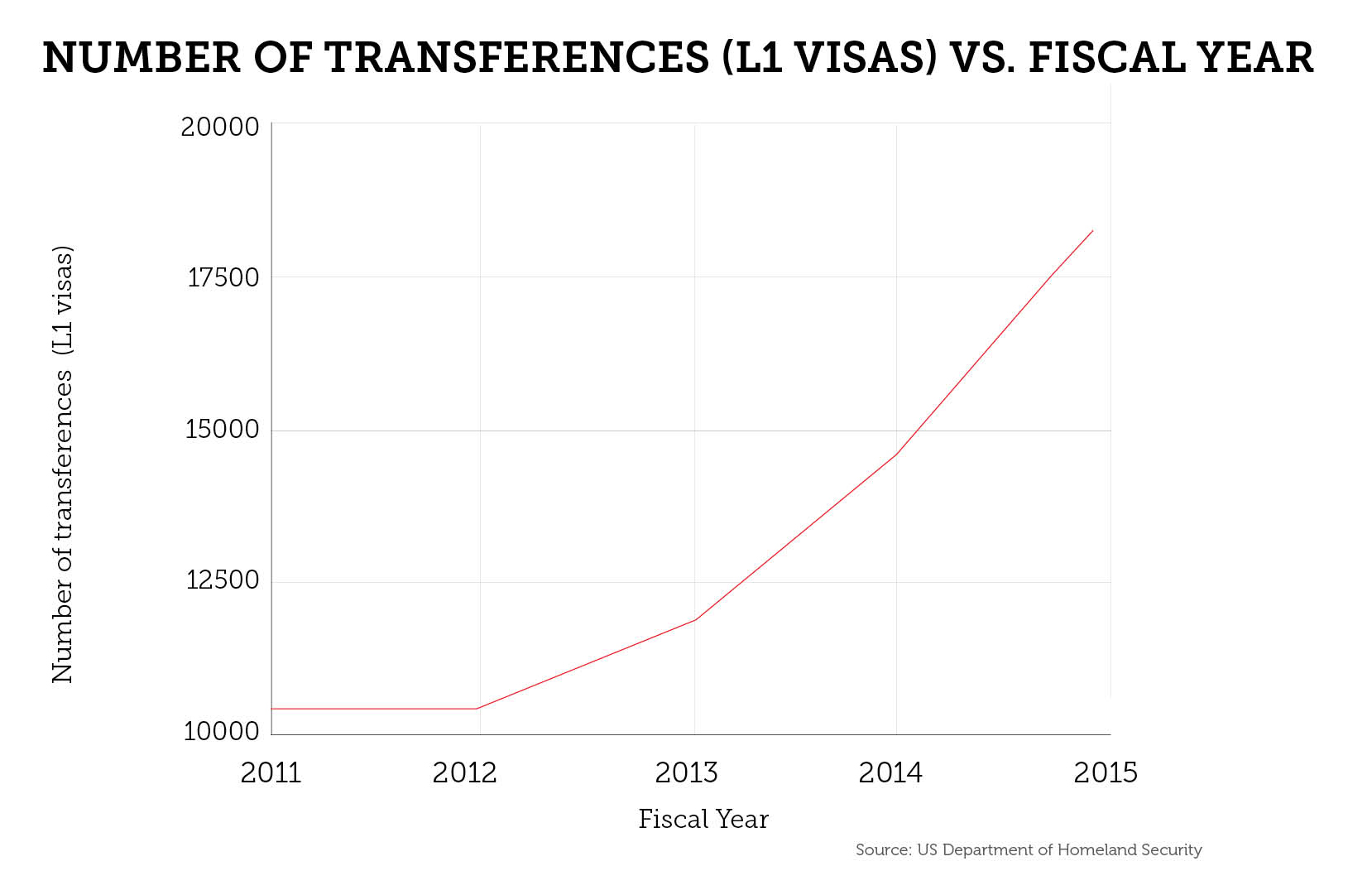

Between 2012 and 2014, there was a 40 percent increase in the number of Brazilians who entered the U.S. after being transferred by their employers from offices in Brazil, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. This influx has contributed to the total number of Brazilians coming to the U.S., which has now increased for the seventh year in a row.

Adding to this rise in migration is tourism. According to Export.gov, in 2014, 2,264 million Brazilian travelers visited the United States, which represents a 10 percent increase over 2013. Now, an increasing number of visitors from Brazil are overstaying their visas.

According to the Department of Homeland Security:

2014: More than 28,000 Brazilians overstayed.

RELATED CONTENT

2015: More than 36,000 Brazilians overstayed.

2016: 37,000 Brazilians overstayed.

The influx of migrants coincides with the challenges facing Brazil. Headlines focusing on new corruption scandals are seen almost daily while the unemployment rate skyrockets, fanning the flames of Brazilians’ frustration with the nation’s government.

Peter Spiro, an immigration law professor at Temple University, said the increase in Brazilians entering the U.S. is expected because immigration tends to increase when countries fall on difficult times.

“That fits historical patterns of immigration,” Spiro said. “When things get bad at home and things are okay in the U.S. then people have more incentive to come here.”

Many Brazilians who work for international companies and want to leave Brazil ask their employers if they can be transferred to offices in the U.S. In this case, the worker is granted an L1 visa and can bring family with them. The number of L1 visas issued to Brazilians increased 15 percent between 2013 and 2015.

Alexandre Gaske, a director at software company SAP, is another example of someone who decided to leave Brazil due to the country’s economic and political climate.

Alexandre Gaske, a director at software company SAP, is another example of someone who decided to leave Brazil due to the country’s economic and political climate. Unlike the previously mentioned 45-year-old professional, the company that Gaske works for didn’t close. He was safe in his position at SAP’s Sao Paulo office but frustrated with the way the country was being run. He decided to apply for a transfer to the U.S.

“I didn’t want to give money to a corrupt government — not Dilma, not Aecio, no one,” Gaske said, referring to the most prominent candidates from the last election. “I want to pay taxes to a government that works for the population.”

Although international workers in the U.S. have recently been portrayed as a threat to job opportunities for U.S. citizens, the U.S. has a lot to profit from this migrant workforce, according to Dr. Kevin Fadl, assistant professor of Legal Studies in Business at Temple University's Fox School of Business.

“Brazilians that are in the United States on a visa that includes work authorization are usually skilled workers that fill unmet demand for skilled labor in the United States,” Fadl said.

“Quantitative restrictions on migration mean fewer foreign workers competing with Americans,” he continued. “But it also means fewer innovators, fewer entrepreneurs, and fewer workers to take the positions that Americans don’t want but that keep the American economy moving.”

LEAVE A COMMENT: