Sci-fi, saints and interventions on the U.S.-Mexico border

"We held a procession for a fictional saint. Saint Stella was a saint to which you could pray to for technological problems you may have in the future."

Before I ever met Pepe Rojo I had heard stories about him. Like how he had typed a few lines of a short story onto a feminine hygiene product, photographed it, and used it as a page in one of his chapbooks. Or how he did the same thing with rotten vegetables. And how he’s always drinking a Coca-Cola and smoking Marlboro reds. I was introduced to Rojo in Tijuana last year, and we got so lost in a conversation about science fiction and border politics that I never got a chance to ask him if his kids think he is weird.

Rojo has penned hundreds of short stories, essays and articles in both English and Spanish. He has published four books and edited two anthologies. His first work of fiction — which he describes as “cyber-punkish horror stories” — was published in Mexico City, where he got his start on the underground scene in the 1990s. There is a performative aspect to his work, whether it's in his teaching or in the staged “interventions” or in the mixed-media books themselves. (You can read one of his stories here in both English and Spanish, but you won’t have the same experience reading Rojo on a screen as you will with the visual object in your hands.)

Today, Rojo says he’s busy making connections — coincidences, he calls them — on both sides of the border. Two weeks ago, he passed through Philadelphia en route to a conference. He had co-authored a paper with musicologist Alejandro Madrid on the Mexican alternative rock group Cafe Tacvba, which was presented at a seminar on experimental music in Latin America at Rutgers University. But before that, he gave me some time for an interview.

Tell me more about the art scene in Mexico City in 1990s. What was the city like back then? What was everyone doing?

Mexico City was a very grave, very problematic city. (Now it’s much better, much greener.) There was an independent press called "Moho." The publisher's imprint in all of their books said "printed in a country in ruins." It was kind of bleak. But there was this underground scene that knew how to party. Independent music and publishing were growing. It was lots of fun, we were conquering different spaces of the city.

Were there common themes in the work that was surfacing at the time?

There was a lot of what they call “junk literature,” because it was about lots of drugs, capturing these little moments in the life of the city. I was also part of the science fiction underground scene, so there was a lot of experimenting going there. There were a lot of groups playing rock and incorporating traditional Mexican sounds into their music. It was difficult, because there was no money at all, but it was thriving.

Today you’re still engaging with a lot of non-mainstream experimental forms, especially the performative and communal aspects of writing. Where are you at right now?

Oh my god, that’s difficult. When people ask me what I do, my most honest answer is I don’t know. Because I try to keep my eyes and my brain and my feet in so many things. The science fiction part of my work is very in love with the human relationships with technology. I try to picture as much as I can of visionary environments.

I also love to make little objects, visual objects whose design is as important as the writing. I try to combine both writing and images, which probably comes from my background in comic books. I don’t know how to draw, but there’s a visual narrative language that I incorporate into my work.

Right now I’m writing my way through a book that’s written on a typewriter on different types of material. I pick up material from the streets and from my house, and I try to typewrite on it and then photograph it.

Do your kids think you're weird for what you do?

Oh, they definitely think I’m weird. They know I’m weird, and they deal with it like “oh, it’s another one of those dad things.” One Halloween I was home alone and I had to find something to do with them. I was like, what do I do? What do I do? They love to get dressed up. So I was like, okay, please, each of you, write a story about how you would kill me.

So they put makeup on me and then photographed me as if it were a murder scene. So now I have this comic book of photographs about how each of my kids would kill me. It was lots of fun. They got really caught up in the excitement of production, too. It was totally weird and maybe inappropriate, but it’s also very nice that my kids know that I do that kind of stuff … And that they shouldn’t be afraid of becoming weird.

They’ve been to a lot of my “interventions.” And they hate readings. Oh no, we have to go to that reading? Yes. I go to your school dances, you have to come to my readings.

Speaking of your interventions, these big collective projects. When we met in Tijuana, you were doing one about the borderlands with a group of students.

Yes. A big part of my work is what I like to call “collective imagination experiments.” Getting a lot of people together and trying to do one project together as a collective voice. My wife Deyanira Torres and I started in Mexico City doing an intervention with a group of 40 people. We pasted 13,000 posters with 13 different designs all over the streets. They all said “Tú no existes,” you don’t exist.

I did one with students in San Diego, and another much larger one with Tijuana students. The nature of the project was to imagine the future using mixed media performance. We held a procession for a fictional saint. Saint Stella. Saint Stella was a saint to which you could pray to for technological problems you may have in the future. For example, you have kids and give them fertilizing drugs to grow an extra nipple — that’s the saint you pray to. So we made this procession on the streets of Tijuana. The guys wrote prayers and they prayed them in public. We had a figure of the saint. It was crazy.

People would start coming up to us and saying, do you have a temple? Can I attend? How can I get baptized? Can you pray for me? We made Saint Stella’s whole backstory. She was a clone and she fled from the states to Tijuana. There were 10 interventions like this, with over 200 people involved.

The interventions strike me as very specific to their place in the country. What are the differences between the literary culture in the south, central, and northern regions?

It’s geographic, cultural and economic, without being able to completely differentiate between them. For example, I go to a lot of writing congresses like that in Mexico. There are fewer in the south. There’s not a lot of budget or interest in the south. It is the poorest and the least educated, but it is also the most populated and the most tied to pre-Hispanic roots. Whereas in the north, you have no pre-Hispanic sedimentary civilizations. You have a desert, a jungle, and a lot of culture. And Mexico City is like this centralized magnet of everything which serves as a center for the whole thing. There’s been a big debate about northern Mexican literature as a genre of its own, different from both the center and the south. That debate also has to do with a particular type of narco culture.

It’s interesting that you mention the landscape. We’ve talked before about how the presence of the border and how it figures into your projects. Is it a specifically northern concern?

It’s a big reference everywhere in the country. Entire populations migrating. The male population. There are towns without men, which is kind of crazy. The relationship with the states is a very complex one. Providing flesh and work to a first world nation is part of an economic arrangement that keeps at least the southern part of Unites States going.

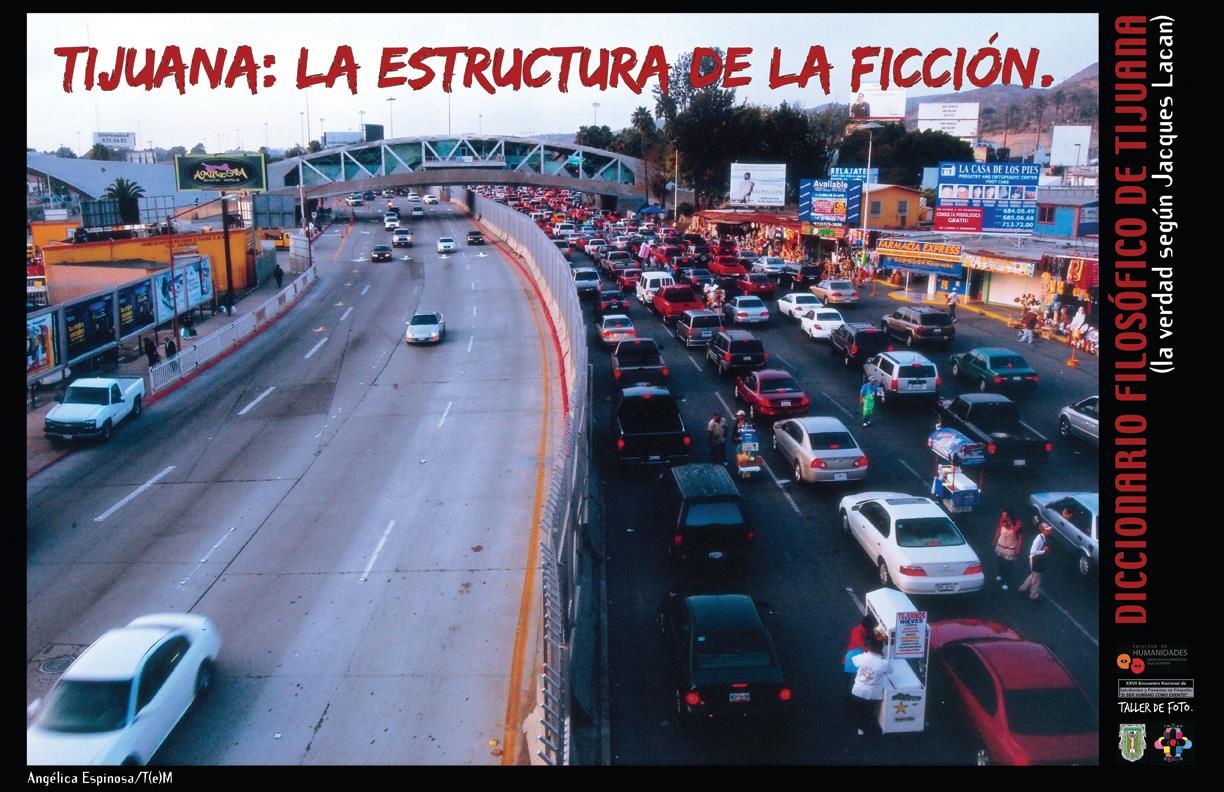

This border, which takes a lot of money to maintain, is completely arbitrary. We keep that reality alive. This is the only place where the first and the third world meet, shoulder to shoulder. Tijuana is the most potent place to see that, because it touches one of the biggest rural economies in California.

You’ve tried and asked others to try to reimagine the border as something else. Do you think it is possible to view it as anything other than a political apparatus?

I think it’s highly political — not in the sense of party system. You have all this telecommunication technology for crossing the border that allows you to go through the checkpoints with just a cell phone and no problems. But at the same time, you have this wall where the natural body is prohibited to cross.

You go through the border and there are all these signs selling you communication packages. There are signs about the medical tourism industry in Tijuana. There are signs by lawyers. The signs point both ways. It’s really exciting and complex and difficult to understand. It’s also very dynamic. It’s changes...It changes...It changes.

Bruce Sterling [the science fiction writer] said that the border is a juice strainer separating bodies from capital. I really love that, because yes it is a strainer.

The duality that the border creates affects your daily life in obvious ways. How does it affect your thinking?

A lot has been made of the border as this hybrid creature that has two cultures at the same time. People in Tijuana are too much like United States citizens to be accepted by Mexico, and too much like Mexicans to be accepted by the United States. So there is this liminal space that has to do with the border — you’re neither here nor there. But it’s also kind of like virtual reality. It’s the place you are when you’re on the phone. There is, of course, this law enforcement that says “you are definitely there.” But at the same time it’s porous. People come and go a lot.

You write and translate in both English and Spanish. You have a foot in two literary cultures. Do you see yourself continuing to build an invisible or physical bridge between two artistic cultures?

There’s a lot of interesting things going on in Mexico that I think a lot of people in the United States would be fascinated to see, and vice versa. Going back and forth between borders I’m getting people to meet. I think that’s part of my job. Alan Moore once said that writers are creators of coincidences. I really like that idea. When you’re writing something, you’re trying to make connections between things, places, characters, actions. But sometimes I feel like to make that happen you don’t even need to write. It only takes introducing two people together in one space and getting them to enjoy themselves, and then it carries into the future. I try to think of myself as someone who creates those coincidences. And translating both ways is another way to make it happen.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.