Race, love and "unbearable" mothers: A story of Romeo & Juliet in the 21st century

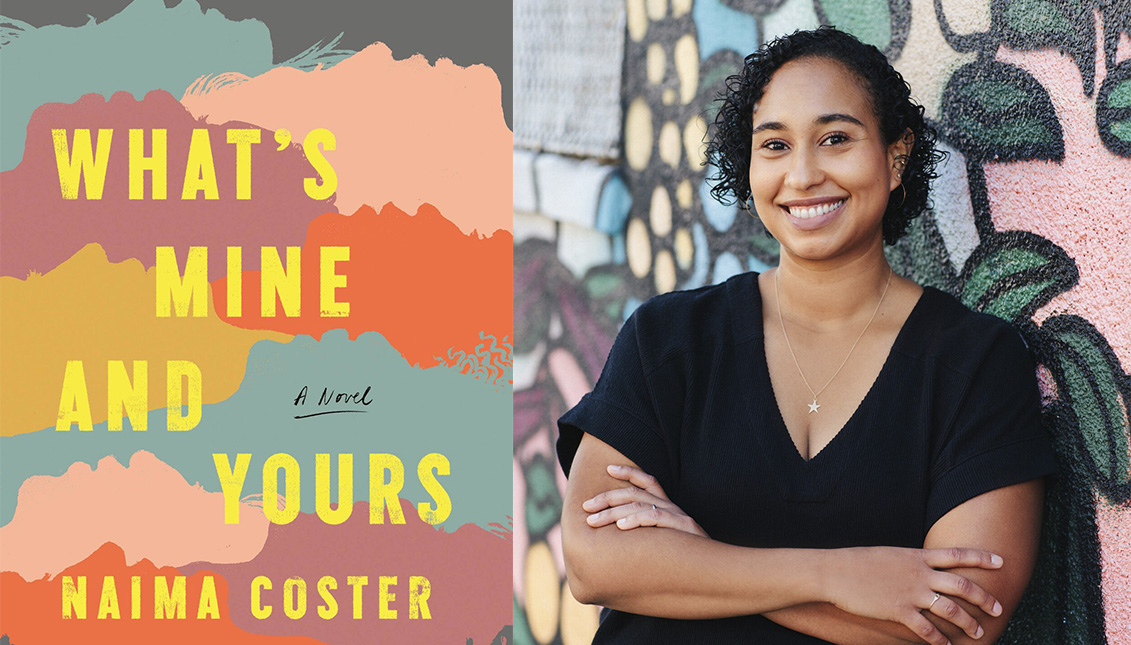

Latina writer Naima Coster's second novel, What's Mine and Yours, is a display of empathy through a story where nothing is monolithic, least of all identity.

In the beginning of a good novel, as in the first scenes of a movie, the author's thesis is usually condensed. As when Tolstoy wrote in the now well-known beginning of Anna Karenina: "All happy families resemble one another; but every unhappy family has a special reason for being unhappy."

Leaving aside that unhappiness or happiness is more than a characteristic, something subjective, a process a person goes through, the opening scene of What's Mine and Yours, the second flamboyant novel by Dominican-American writer Naima Coster lays the groundwork for a story about race and identity as something that both unites us and separates us, even sometimes from our families.

We are in the Piedmont Triad of North Carolina on a day in 1992. Two men smoke outside an empty cafe as they tell each other, to pass the time, stories of their respective families, unaware that those same families will eventually be brought together by misfortune.

A 2018 Kirkus Fiction Prize finalist for her debut novel Halsey Street and considered one of the best authors under 35 in 2020, Coster, delves into the style of Russian classics and her talent for building complex characters and immersing the reader in their particular psychology, a choral story of two families whose fates intersect when a county initiative desegregates the high schools and brings black kids from the east side to the west side of the mostly white city.

Like a sort of Romeo and Juliet, Gee, a black kid from the east side who enters the new west side high school, and Noelle, a biracial Latina teenager who passes for white, are doomed to fall in love and also to put up with each other's mothers. Jade, Gee's ambitious mother, only wants her son to thrive in a better desegregated school; while Lacey May claims that her half-Latina daughters are white and is against school integration.

However, Noelle feels more Latina than her own family, and also meets Gee in a school play that aims to bridge the gap between these new students from the East and the high school veterans, which means that two families in opposition from the very beginning - although that conciliatory cigar hints at other things - begin to form bonds that will govern their children's destinies and mark them forever.

Because we are nothing more than the past, because what is sown in childhood and even what is sown by our ancestors remains firmly anchored in our consciences and even our DNA, and emerges in different forms over the years and in different places.

In this case, North Carolina and also Atlanta, Los Angeles and Paris, across multiple generations and years from 1992 to around 2020 when the lives of Gee and Noelle, who seem to have reached the same status, collide again. But childhood, as Coster explores, is too wide a chasm for anyone to dare cross.

As an Afro-Latina who grew up in Brooklyn and won a scholarship to attend a mostly white and private high school, Naima Coster knows firsthand how complex it is to delve into how this process of forced integration.

"It was an experience that certainly opened doors for me," she told the Star Tribune. "Less is said about the difficulties of that experience when you're one of the only children of color in a mostly white space. Or what it means for your family relationships to be the only one in the family who makes it the furthest."

While Coster admits that segregated schools perpetuate inequality, Gee's character in his novel experiences the contradictions of this opportunity, because while attending the new majority-white high school has opened doors for him as an adult, "he is also haunted by the question of whether he deserved what he got when others in his family couldn't. It's a heavy burden. It's a heavy burden".

RELATED CONTENT

Naima Coster also had to deal with this sense of responsibility. Although she had been writing since she was a child and fantasized about becoming a writer, she felt the pressure to study for a "lucrative and stable" career and sent applications to medical schools. Fortunately for literature, she realised her dream and ended up pursuing a master's degree at Columbia University.

A reader of Edwidge Danticat, Angie Cruz and Patricia Engel, their books inspired her and made her believe that the stories she wrote would one day reach their readers.

"I think there are a lot of families - mixed and otherwise - where different people in the family have different relationships to their identity even though they share a common heritage and common roots."

As happens in the stories of its predecessors and companions on the road, at the heart of What's Mine and Yours is racial identity.

In Coster's novel, Noelle, who is white, identifies as Latina and confronts her mother, something the writer says is common to many biracial families.

"I think there are a lot of families - mixed and otherwise - where different people in the family have different relationships to their identity even though they share a common heritage and common roots," Naima states.

Even in her own family, the author has had to deal with these kinds of complex issues that show that identity is not a monolith and neither is race.

"In my family, I know siblings who identify as different races, even though they share the same set of parents. My own parents were Latinx (a neutral term for Latino) and Caribbean, but only my father identified as black," concludes Coster.

In short, What's Mine and Yours is a novel that gets the reader asking questions, settles debate and creates empathy through both humor and impeccable prose, but also explores identity in a rather unique way by getting inside the minds of its characters, even if at times its unique structure can be confusing. As much as the very notion of identity, family or love.

LEAVE A COMMENT: