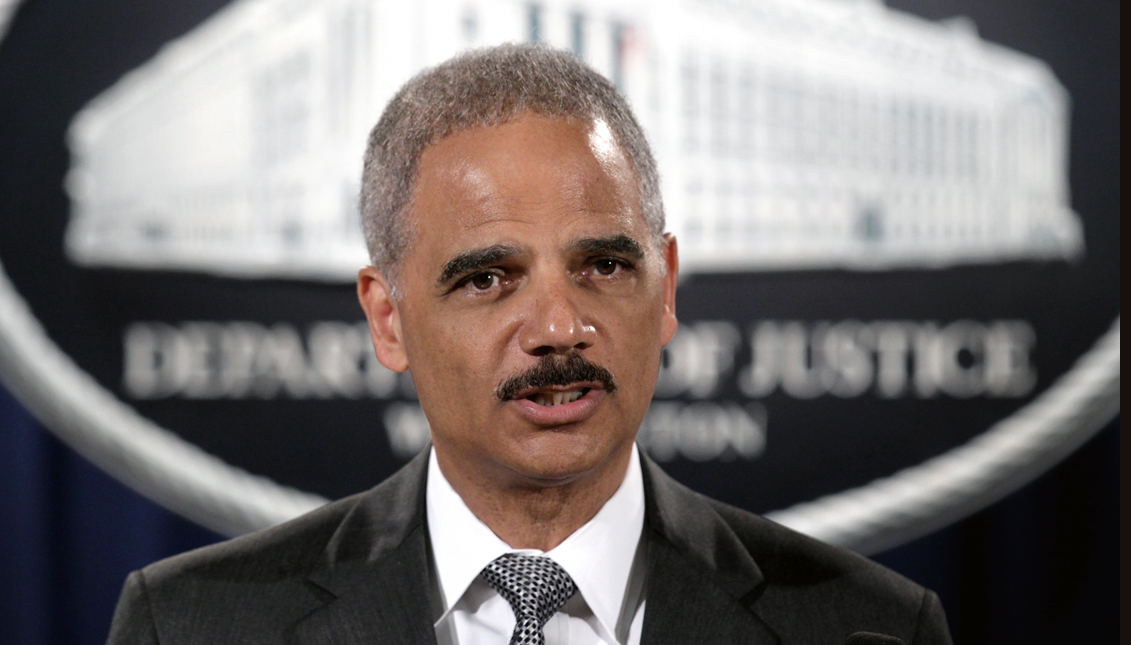

Redistricting, gerrymandering and voting in 2020 with former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder

The chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee said the 2020 election is unlike any in his lifetime.

“People have to understand that what is going on right now is not normal.”

That was what former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said in a recent virtual call with AL DÍA responding to a question about the actions of the U.S. Justice Department under current Attorney General, William Barr.

Holder was referring to Barr’s propensity to do the president’s bidding as a part of his cabinet rather than serve the American people as Attorney General.

But Holder’s answer extends beyond just the Justice Department.

2020 has not been a normal year, in politics and in just about every facet of life one can think of thanks to the coronavirus pandemic.

It’s featured a census count — that recently got an extension — and in almost storybook fashion, will end with a presidential election in November.

Both are what brought Holder to his virtual conversation with AL DÍA on Sept. 15.

As the chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), he and the organization have a lot riding on the final three months of the year.

The organization’s goal is to create a comprehensive redistricting plan that will eliminate gerrymandered districts and create more competitive election circumstances for those running for office.

Redistricting happens every 10 years following a census, and is the redrawing of electoral lines for both the House of Representatives and state legislatures.

At the federal level, per the U.S.’s congressional apportionment process, each state is granted at least one of the 435 seats in the House of Representatives, leaving 385 to be divided among states based on their total census-reported populations.

State legislatures then redraw their own electoral lines along with those of their state’s federally-apportioned (granted) districts. In some states, the maps must then be approved by governors.

“We redistrict as a country, but it’s done on a local basis,” said Holder.

For the NDRC, it’s why the 2020 census is so vital.

“We need a full and accurate census count to have a fair redistricting process,” he said.

That especially includes traditionally undercounted groups like the Black and Latinx communities.

“People in communities that are not counted will not have representation,” said Holder.

In the event of an undercount in 2020, no population stands to lose more representation than the Latinx population, and Holder said it was “telling” that the Trump administration targeted Latinos throughout the census process with policies like the ill-fated citizenship question, or a recent attempt to bar undocumented immigrant data from the redistricting process.

All were geared toward decreasing Latinx turnout and potentially setting back their representation in the country for the next decade.

While legally, the government’s system of checks and balances have curbed the administration’s attempts to outright exclude members of the population from the census, the 2020 decennial count has also had a pandemic inhibit much of its in-person efforts.

“It’s been problematic,” said Holder of the effect of COVID-19 on data collection.

But he also took the same view of the Trump administration’s politicization of the census process.

In addition to creating a “climate of fear” around filling out the census that will affect counts, the resulting undercounts will also allow the administration to further silence those populations subject to its threatening policies.

That silencing is done for political advantage.

Holder said that before Trump’s administration, using the census as such was unheard of.

“It is this administration that made a determination as a political advantage,” he said. “I hope what we’re seeing right now is an aberration.”

Voters will decide whether that “aberration” continues on Nov. 3.

However, some will have more of a voice than others thanks to gerrymandering, which is the core issue Holder’s NDRC is out to fight.

“Gerrymandering at its most basic level is just cheating,” he said.

To expand, gerrymandering is when one political party manipulates the redistricting process of redrawing electoral maps to benefit itself at the expense of the people and other parties.

The result is that some voters have the impact of their votes muted.

“Gerrymandering weakens our democracy by making some voters’ ballots more powerful than others’ by eliminating truly competitive elections,” said Holder.

In recent history, the gerrymandering war has primarily raged between the Democratic and Republican parties, with the latter proving more adept at the practice.

Following the 2010 census, Republicans rode a red wave in state legislatures to redistrict large parts of the country in the party’s favor.

Those effects were felt in both 2016 and 2018, as Republicans won more congressional seats than would be suggested by the share of votes the party received. In 2018 particularly, the party won an estimated 16 more U.S. House seats than would be expected, according to an AP analysis.

Politically, gerrymandering also reinforces the polarized climate that’s been given rise with the ascent of President Donald Trump.

Those representing a gerrymandered seat are more concerned with a primary challenge than one in a general election.

“If you’re in a safe seat, there’s no electoral consequence,” said Holder.

As a result, those representatives tend to also serve more of the party’s extremes and special interests, even if a solution has bipartisan support.

RELATED CONTENT

For example, Holder recalled a bipartisan immigration reform bill that had passed the Senate in 2013, but was stonewalled in the House by members of the Freedom Caucus — a more conservative wing (for 2013) of the Republican Party.

The group gave similar trouble during an effort to expand Medicaid in spite of its bipartisan support.

“They do these things knowing there is great support for Medicaid expansion, great support for comprehensive immigration reform,” said Holder.

Most of the Freedom Caucus members came from gerrymandered districts, he said.

So what can be done?

Legally, the Supreme Court has ruled in favor of doing away with racial gerrymandering, but will not decide in cases of partisan gerrymandering, which often still leave communities of color out of the loop.

As a result, Holder said all of NDRC’s fights in the court take place at the state level.

Nationally, the organization also has a number of reform proposals for the process, such as appointing a nonpartisan commission in place of state legislators to redraw electoral lines.

But most importantly for Holder, the way to combat gerrymandering is to vote.

He was honest about the reality of that approach.

“If you’re in a gerrymandered district, your vote probably isn’t worth as much as someone in a contested district,” said Holder.

But while a single vote may fall as a consequence of gerrymandering, there is power in numbers.

“If communities vote in total and in substantial ways, that can really have an impact,” said Holder.

That can be difficult for communities that already feel disenfranchised by their government.

Still, Holder says the only way to have a voice is to use it.

“As hard as it might be for people to see the change happen, I can guarantee that the change will not happen if you don’t vote,” he said. “We have to fight.”

When it comes to voting in 2020, Holder said it’s beyond just doing it. With all that’s swirled about the effect of coronavirus and mail-in voting, voters need to have a plan.

For mail-in voting, Holder said to request a ballot as soon as possible, if voting in person, check to see if your state has early voting.

“Do not wait until the last minute,” he said.

In 2020, NDRC has endorsed candidates running in state elections across 13 states that have the worst cases of gerrymandering — among them are battleground states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. The hope is that if these candidates win, the redistricting process of 2021 will result in fairer electoral lines.

That fight ends on Nov. 3.

“This is going to be an election unlike any in my lifetime,” said Holder.

LEAVE A COMMENT: