Violence in Ciudad Juárez: An artist’s response

On display at The Print Center in Philadelphia through March 21, an exhibition from Miguel Aragón explores the limits of documenting violence.

Giving form or narrative to violence — for artists, for journalists, for historians — is neither easy nor simple.

To set down the details of a crime, of a single loss of life, let alone hundreds, is too complicated a feat to be taken lightly, and it doesn’t lend itself to facile forms of representation. There is no right way to depict violence, but there are certainly many wrong ways to record trauma and tragedy, which can often be more damaging to those most affected, despite the best of the artist or journalist’s intentions.

Artist Miguel Aragón is no stranger to the struggle to contend with representation of violence, and its impact on those who experience and witness it on a daily basis.

Aragón grew up in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, a border city of 1.4 million people that has one of the highest murder rates in the world for cities that are not located in active combat zones.

Nearly 1,500 people were killed in Ciudad Juárez in 2019, the fourth-highest amount of homicides ever recorded in the city, and the highest number the city has seen since 2011, during the government’s declared war on drug cartels, which left 1,967 dead that year.

In the face of the relentless reports of those killed, many of whom are individuals often noted only as numbers in the newspapers, Aragón seeks to create artworks that address the silence represented by those whose lives have been lost.

Out of this effort comes “Indices of Silence/Índices del silencio,” an exhibition which, though small in the number of pieces presented, is vast in its reach and impact as it tries to give some shape to the deafening void produced by that violence.

Chosen as one of three exhibitions for The Print Center Philadelphia’s 94th Annual International Competition on view from Jan. 17 to March 21, “Indices of Silence/Índices del silencio” is a powerful meditation on the depiction of violence.

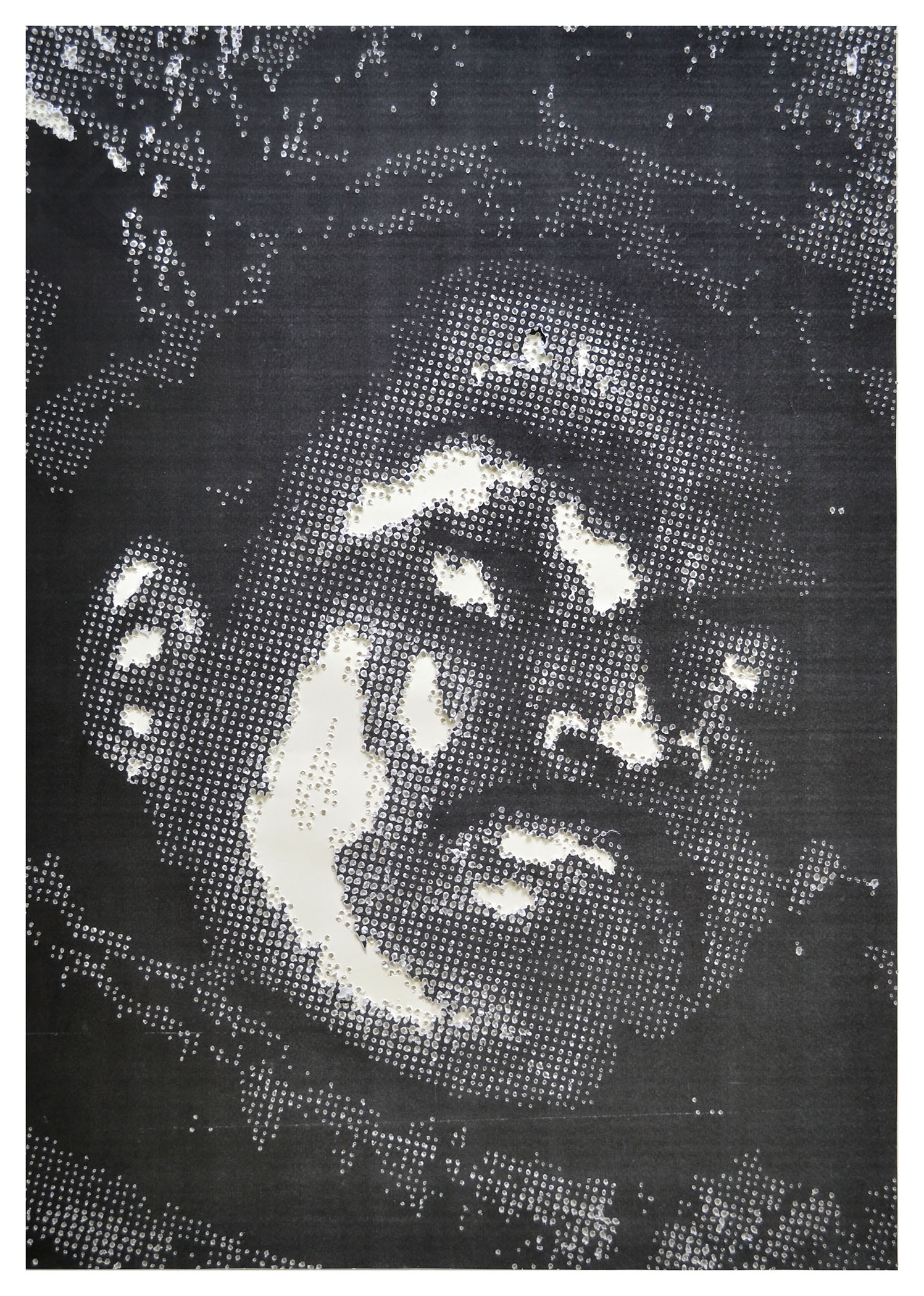

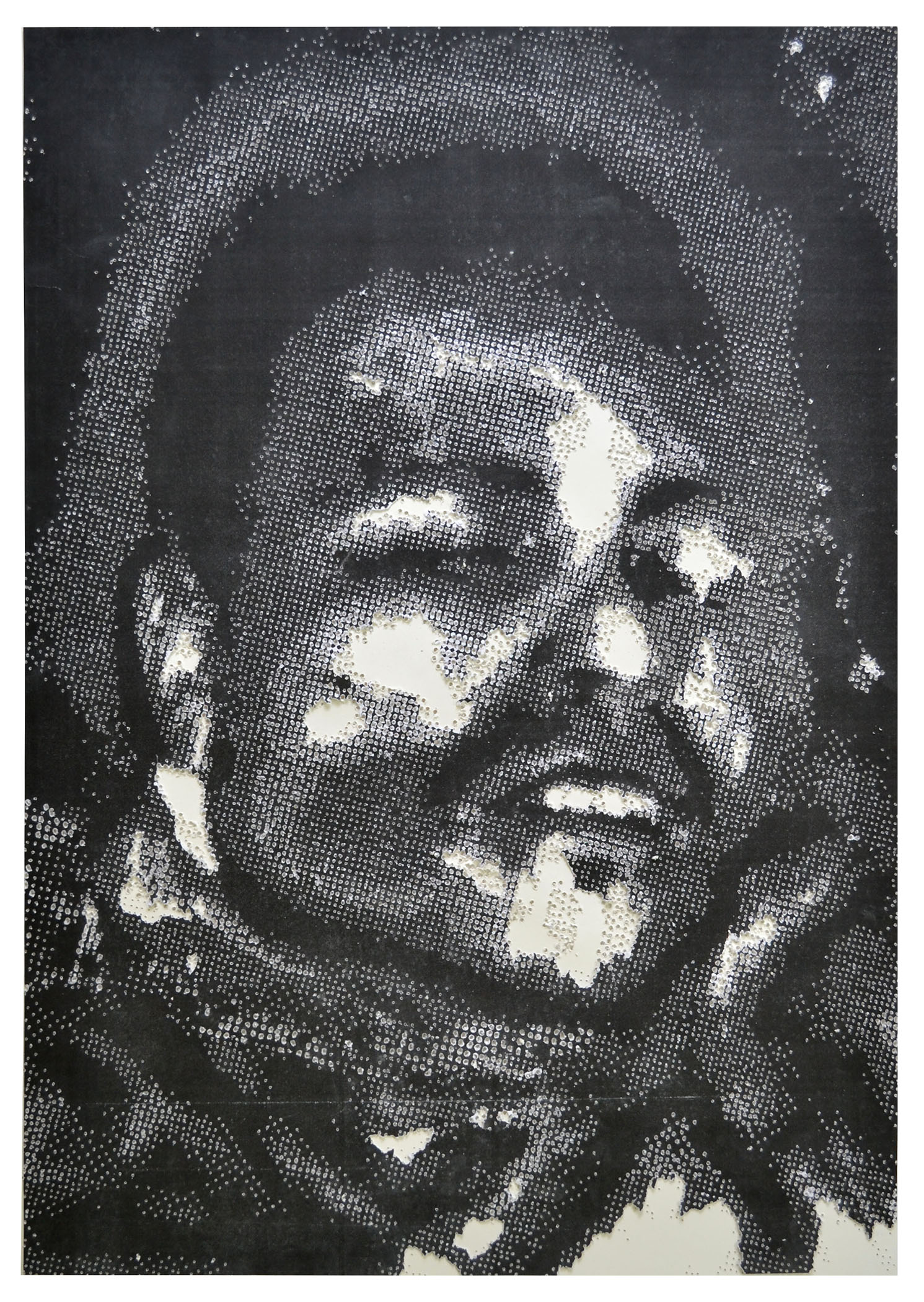

When viewed up close, the large sheets of layered xerox matrices or hand-cut woodblocks featured in the exhibition resemble an abstract landscape of dotted black and white layers. From several paces away, though, their true subject materializes.

Faces, with eyes closed, are spelled out in intricate designs in the prints made with drills. They are the victims, many unidentified, who are among the thousands slain each year in Aragón’s home city — at times left behind at a morgue, not even claimed by family members out of fear of retribution of drug cartels.

As recently as Jan. 2, the government of Chihuahua, the state where Ciudad Juárez is located, announced that it would be constructing a new 50,000-square meter “mega-cemetery” that will enable the city to better attend to and put to rest the remains of the many people killed by the ongoing violence, especially those who remain unidentified.

It is a sad, tangible representation of the persistence of the violence: As an estimated U.S. $2.65 million will be invested in a way to accommodate the bodies of the many people killed, the structure embodies a necessary surrender to an unavoidable reality that has no end in sight.

But Aragón, as he says in his artist statement, tries to question that inevitable reality of death and violence through his pieces, in which the faces of homicide victims, punctured by drill holes, appear in repose, indistinct, and blurry. For all that their features are seemingly erased, the portraits, larger-than-life, have a magnetic presence; they demand attention and scrutiny, compelling the viewer not to look away. In Aragón’s words, this is possible because “any form of erasure, however violently destructive, can be seen as constructive in some way; something comes through the destruction, the negation of an image is not actually nothing.”

Through erasure, Aragón is trying to restore the humanity of those killed to the images of their death, and, perhaps, create a route to imagining a city in which a “mega-cemetery” would not be needed; thousands of people would not have to watch their loved ones die or fear that they be killed; and young men would not be compelled to turn to what they see as “easy money” via narcotrafficking in order to simply survive.

Long before they became images in the printmakers’ work, the faces of those found dead were a fixture in Aragón’s mind, and the object of his fascination.

“From when I was small, for some reason, I can’t explain why, but I was always drawn to reading the news in the newspaper about when they found cadavers...Eventually, when this really became a huge problem in the city, it had such an impact that I could no longer ignore it,” Aragón said.

When Aragón was growing up in the 1990s, the homicide rate hadn’t risen as high as it later would, when an official war on the cartels was declared in 2006, but there was still violence related to the drug trade. Juárez, due to its proximity to El Paso, TX, and the Mexico-U.S. border, was a well-traversed corridor for drug smuggling.

At the end of 2006, then-President Felipe Calderón launched what was considered the first major offensive in the government’s war against narcotraffickers, setting off a wave of violence that reached its peak in 2010, with more than 3,000 murders. As the drug war heightened, Aragón began creating works about the violence he had witnessed in his hometown since childhood. But though he tried, “nothing came out well.”

He later left for Austin, TX, to do his MFA at the University of Texas at Austin, which he graduated from in 2012. The change of environment had an impact on his attempts to make art about his home city.

“It was the first time that I left the city [Juárez]. I think that that helped me to have a little bit more vision and see things...with more perspective. It also helped me to find different techniques in order to be able to create an artwork more carefully, in some way,” Aragón told AL DÍA at the opening of “Indices of Silence/Índices del silencio” on Jan. 16.

While pursuing his MFA, Aragón explored new tools and mediums that fused technique and idea in a way that “would be strong, would be powerful for viewers or the audience.”

Though geographically farther from Juárez than he had ever been before, he delved even deeper into researching the crime plaguing his cities.

From Austin, he watched news clips online, or studied newspapers his mom would send him directly by mail from Juárez.

“I spent a lot of time looking at these images and reading these stories...there were so many brutal images that I saw, that what I wanted to do was erase them,” he said.

He developed the technique of using a handheld drill to puncture xerox sheets with faces of murder victims printed on them, “in order to try to erase the image” by creating white holes in the image. It was at once to make the image of a victim’s face disappear, and appear again in another form, Aragón explained.

The effect is eerie, as the viewer is almost led to think of wounds caused by bullet holes — an effect that Aragón said he did not intend, but now cannot deny.

“It became very obvious when I began to create pieces that I was in some sense becoming a surrogate of being with violence, creating an image that talks about violence,” he said.

Out of this desire to erase the graphic images of death, and to at the same time humanize the many people who were recorded in newspapers as only numbers, without names, Aragón began to develop the concept of how he wanted to address the topic in his work.

RELATED CONTENT

“These techniques came from there, from really trying to erase these images from my memory, but at the same time also that the image becomes something different. To take away this idea that it was a violent act and recreate it as something more, something wholesome, in some way. More than anything, to humanize these cadavers,” the artist said.

Some of the victims were police officers; others, narcotraffickers; and some were innocent bystanders who were not involved in either side of the government-cartel conflict. It bothered Aragón, though, that no matter what, they were only ever referred to as numbers in the press reports about homicides.

Since an overwhelming number of victims’ bodies aren’t identified, and family members hesitate to come forward to claim those of relatives from the morgue out of fear of retaliation from cartels, many of the slain individuals are simply identified by their number and are often presumed to be cartel members.

“At the end of the day, they were someone’s father, someone’s brother, an uncle, a friend, and more than anything else, they are generations of men that we are losing in Mexico who are between 20 and 40 years old,” Aragón said, noting that it is now a problem that is affecting many communities and cities in Mexico, not just Ciudad Juárez.

Aragón, currently a professor at CUNY College of Staten Island and an internationally-recognized artist whose work is held in private and public and collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago; and Minneapolis Institute of Art, has shown his work at galleries around the world.

Though he still hasn’t shown his work in Ciudad Juárez, Aragón said that many people from Juárez attended an exhibition that he held in El Paso, TX, just across the border, a few years ago.

There, and at another exhibition that he held in Mexico City, Aragón said that he met with family members of those who had been directly impacted by the violence and lost loved ones in Juárez.

“Honestly, I was very afraid of how they were going to react to my work,” Aragón said. “Fortunately, they understood what I was trying to do, and in fact they...supported me, and they told me to keep doing what I was doing because it’s a way of bringing to light what is happening, and that the government understands or that the people understand and change things.”

Aragón added that families affected by the violence said the work that he and other artists — including the internationally renowned artist Teresa Margolles — are doing is “necessary.”

Margolles, whose work is often featured on the world’s largest art stages, including the Venice Biennale, has been creating artwork that grapples with the most unspeakable aspects of crime in Juárez since the 1990s. Margolles currently has an exhibition, “Assassination Changes the World,” on view at Tribeca’s James Cohan’s Gallery in New York City. It examines violence on both sides of the border, including the effects of the mass shooting which took place in El Paso, TX, on Aug. 3, as the alleged shooter, a white man, targeted Latinos in what will be prosecuted as a hate crime which left 22 people dead.

Aragón noted that Margolles and other artists are also addressing the rising rate of femicide in Juárez and throughout Mexico, another issue that has been at the forefront of national and international discussion lately after the murder of 26-year-old artist and activist Isabel Cabanillas in Ciudad Juárez on Jan. 18.

For Aragón, the support of family members who have lost loved ones has encouraged him to continue his work, recognizing that those he portrays are silent, and “can’t speak for themselves.”

“They become numbers that can no longer...explain their motives of why they entered into these types of acts in some way,” Aragón said.

And to that silence, he said, is added “the silence of the country, that now, especially with this new president, is trying to ignore things and that things continue like they’re going to happen.”

Many have noted that since current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, also known as AMLO, came into office in Dec. 2018, violence throughout the country has risen.

In 2019, Mexico saw a record-high of 34,582 murders, according to a report released last month by Mexico’s Secretariat of Public Security.

For Aragón, the answer to the crisis of violence lies not in ignoring it, as some characterize AMLO’s hesitancy to “fight violence with more violence,” or in quelling crime by force, as past Mexican presidents have tried to do.

The solution, he said, has to center on economic investment and job creation for the many young men who have resorted to crime and narcotrafficking simply as a means of survival and in order to provide for their families.

“The problem that these people have is that they don’t have another alternative. It’s the only way that they can get money, so what we need in the country is that the country invests in the population so that everyone is able to get a job and that they can give us a sufficient salary in order to maintain ourselves and maintain our families,” Aragón said.

“Indices del Silencio/Indices of Silence” is on display through March 21 at The Print Center of Philadelphia, 1614 Latimer St. Admission is free, and the center is open from 11:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday. On March 19, from 6 - 7:30 p.m., Aragón will give an artist talk at The Print Center that is free and open to the public.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.