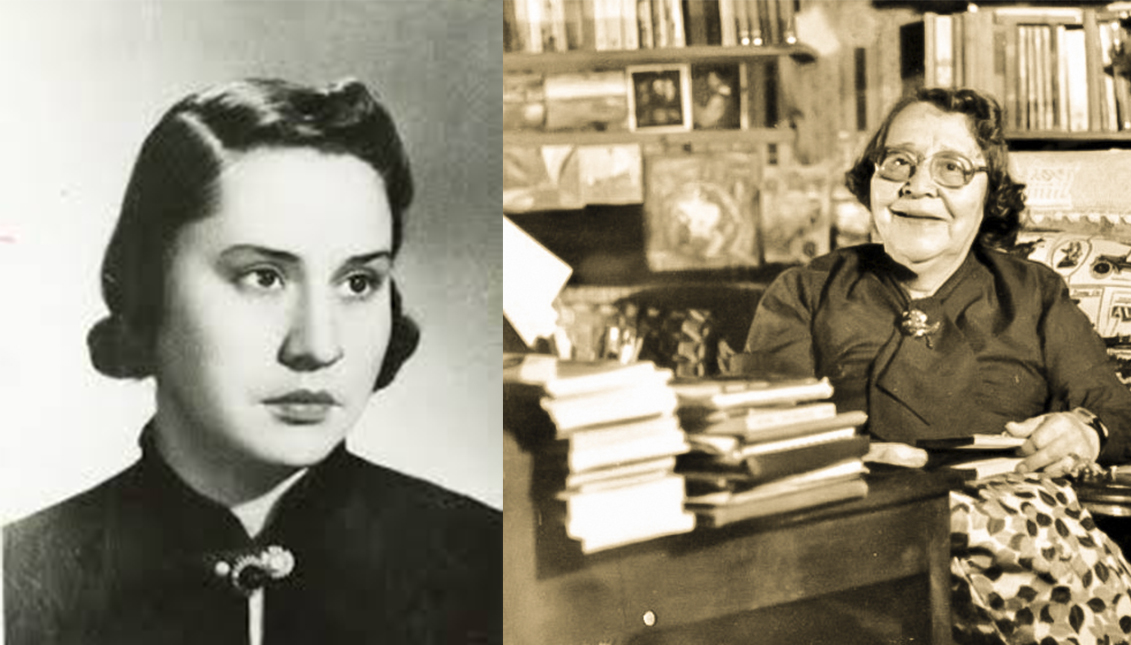

María Elvira Bermúdez, the Agatha Christie of Mexican literature

A pioneer of the crime novel and a lawyer by profession, Bermúdez invented the first woman detective of Latin American noir.

Who knows better the threats that lurk in the streets, the anatomy of a crime and the dark judicial holes than someone who faces them daily?

Like many crime writers, María Elvira Bermúdez worked in the judicial system, in the Supreme Court of Justice and as a lawyer. In fact, she was the first woman to graduate from the Escuela Libre de Derecho with a law degree, and although she loved Mexico City, she knew firsthand what her neighbors were capable of.

"It doesn't take much to say that there are cases of corruption," she once said.

Yes, for her, the mystery novel, a genre that was always despised by high literature, was both a way of denunciation and a tool to express her political ideals. One of them was the struggle for women's rights, especially the right to vote, at a time, the 1950s, when they were the silent victims and men were the spokesmen and perpetrators.

If a woman appeared in a crime novel, she was the cold and violent trigger of the story, the disconsolate widow or the femme fatale who ends up driving the male hound crazy who solves the case. A bit like in Chandler's novels, so in life.

But Bermúdez, it was written, was going to revolutionize everything, although today finding many of her books is the work of a detective. Something that makes her different and like another crime writer, who together with the Mexican opened the way to the ladies of crime, Agatha Christie.

When María Elvira Bermúdez began to publish her stories in 1940, it had been a year since Christie had made a big splash with her And then there were none. Noir fiction was living its apogee in Mexico at the time and Bermúdez began to earn the nickname of the "Mexican Agatha Christie."

RELATED CONTENT

They both had something in common, not only daring a genre in which only men stood out, but introducing perceptive female detectives as the protagonists of their mysteries and murders. In Christie's case it was Miss Marple; in Bermúdez's case, the mythical Elena Morán, a housewife fond of mystery novels, married to a federal congressman, with a gift for solving crimes thanks to her readings.

In Detente, sombra (1961), a detective story entirely starring women - and professionals - Morán must solve the murder of América Fernández, a writer who turns up dead in the apartment of literary critic Georgina Banuet, becoming the main suspect and introducing lesbianism into the story through the motive of the crime of passion.

A striking story, not only because Bermúdez approaches the genre from the literary avant-garde, with a prose that is not at all arid, but because through her characters, powerful women with political positions, she highlights the victories of feminism in those days. A few years earlier, women had the right to vote and were appropriating spaces that had been denied to them. In addition to critically addressing the macho prejudices and morals of a changing time.

Something that contrasts with her first novel, Diferentes razones tiene la muerte (1952), where the motivation for the murder is that the character, a woman, was single and a party animal, which the men couldn't stand. A work starring Bermudez's most iconic detective, and who also appears in many of her early stories, the journalist also fond of noir Armando H. Zozaya. Among its pages, as in other Mexican detective writings, the prejudices of the time are also challenged.

María Elvira Bermúdez not only wrote crime fiction, she also devoted herself to theorizing about the crime genre as did Bioy and Borges in those same years, and even published critical essays about Mexican society.

Near the end of her life - she died in 1982 -, the writer was rediscovered by young people, and those who knew her say she often opened the doors of her old house in the Roma colony to receive friends and readers, while new crimes were being perpetrated on the dark streets of Mexico City or in the even greater darkness of the minds of other female writers.

LEAVE A COMMENT: