[OP-ED] Put Down the Drink and pick up a Book!

Here we are once again. Another Cinco de Mayo, another excuse to pick up a drink and eat nachos. Over the years we have used this factually correct holiday to commercialize the food and alcohol industry in order to see their wallets get fatter and our consciousness of history get smaller. Lets start with the actual history of Mexican Independence Day.

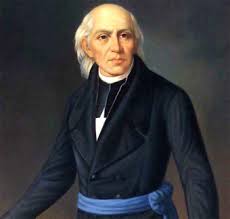

The date was September 16th 1810. In the village of Dolores, a Roman Catholic priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla started the initial spark for the Mexican War of Independence. Jose Bernardo Gutierrez de Lara who was looking for support to separate Mexico from Spanish control approached him.

Hidalgo y Costilla ordered his brother Mauricio to go with some armed men and make the sheriff release pro-independence inmates. They were able to release about 80 prisoners in the early hours of September 16th. Around 2:30 in the morning, Hidalgo ordered church bells rung and gathered people together. In his address to the congregation in front of the church, he urged the people to revolt against Spain.

“My Children a new dispensation comes to us today. Will you receive it? Will you free yourselves? Will you recover the lands stolen three hundred years ago from your forefathers by the hated Spaniards? We must act at once…will you defend your religion and your rights as true patriots?”

The “Grito de Dolores” was not about criticizing the social order of that time but to show his disapproval with the Spanish government as well as showing his support of Catholic religion. After Hidalgo’s speech, his support swelled to over a few hundred people. Hidalgo marched his army through the towns of San Miguel and Celaya where the rebels killed whatever Spaniards were in their way and joining forces with his rebels. Ironically, the Virgin de Guadalupe became a symbol and protector for these Spanish forces.

On September 28th, they reached the town of Guanajuato and discovered Spanish forces barricaded in a storehouse within a farm. By this time, the rebels numbered about 80,000 strong. Around 500 Spanish and Creoles were slaughtered while Hidalgo continued the march towards Mexico City.

His troops advanced as far as Cuajimalpa, which is on the outskirts of modern day Mexico City. His decision to retreat to Guadalajara instead of going into the capital city is still a mystery to this day but this this did not change the outcome of the battle. The victory at Los Lianos de Salazar is considered one of the pivotal battles for Mexican Independence.

CONTENIDO RELACIONADO

The Battle of Puebla has long been assumed in the United States as Mexico’s Independence Day when in actuality it celebrates the Mexican Army overcoming huge odds by defeating a French army that was nearly double its size. A bad assumption became the catalyst for starting the war.

French forces were thought to have been withdrawing to the coast but Mexican Republic forces took the movement of these forces as a threat. Adding fuel to the fire was that negotiations between the two countries had failed. General Lorencez made a tactical assumption that the village of Puebla would fall once a show of force was made.

On May 5th 1862, his attack of the city from the north proved to me a huge miscalculation. Lorencez started his attack in the late morning using most of his ammunition and advancing the soldiers by the early afternoon.

By the third wave of attacks, the French soldiers did not have the artillery support needed to continue their final assault. Mexican forces put up a major defense between hilltop forts in Puebla. The victory was a major morale boost for the Mexican army and became a symbol of unity and pride.

In California, Cinco de Mayo became popular during the 1940’s Chicano movement. During the 50’s and 60’s, the holiday started to make its way throughout the country, but it was not until the 1980’s when marketers, especially beer companies, took advantage of the event to target the Latino population.

Back in 2015, Latino consumers spent around 1.5 trillion dollars on the holiday. One of the two major beer makers, Corona, capitalized on the event by selling more than 145 million bottles within two weeks of the celebration.

Other companies such as the restaurant chain Chili’s and Chipotle give discounts for meals, Avocados from Mexico found an “untapped potential” in using the holiday to gain profit. Even Victoria’s Secret launched a campaign in 2013 that involved “Cinco de Mayo” themed shirts that read “Let’s no taco ‘bout it” and “I know the guac is extra.”

The holiday has been so saturated and diluted by marketers that a majority of people would not give a second thought on it’s real meaning. We need to give emphasis on the cultural significance of Cinco de Mayo in our schools, and within various communities throughout the country and not focus on how much we can make selling edible sombreros and cases of beer.

DEJE UN COMENTARIO:

¡Únete a la discusión! Deja un comentario.