Ambassador Manuel Torres, the Philadelphian you didn’t know about | OP-ED

He lived in our midst for over 30 years. Today, however, few know he was the most prominent Philadelphia of Latino descent that has ever lived in the first…

Please allow me to introduce to you, dear reader, the City’s resident of Latino descent “most famously unknown.”

In 1823, he was buried in Old City, his coffin moving slowly along with his few true friends walking in mourning behind, hats in hand, the most prominent residents of Philadelphia at the time in reverence of their deceased dear American from the South.

The most prominent among them was the famous publisher of the Philadelphia Aurora newspaper, Mr. William Duane.

Along with Duane, Mr. Meade, who were the 2 people Torres chose to take care of his estate upon his death.

With them, hundreds of residents in the city and surrounding areas attended the funeral of the deceased man born in Cordoba, Spain, but simply a famous exile from South America in Philadelphia who in 1822 became the first ambassador from a newly created Latin American republic who presented his diplomatic credentials to the government of the United States, then led by President James Monroe.

...He was just a Philadelphia city dweller who represented a key piece of the Southern part of the hemisphere: La Gran Colombia.

In reality, he was just a Philadelphia city dweller who lived among us for more than 30 years, and who perhaps only aspired to be called “just another American," one representing a key piece of the Southern part of the hemisphere: La Gran Colombia.

Only 6 weeks after he was received by Monroe in Washington DC, Torres passed away in his house in West Philadelphia at 2 p.m. on July 15, 1822, at age 59, the Wikipedia entry reads.

It adds,

"On July 17, the funeral procession began from Mr. Meade's house, which was joined by Commodore Daniels, of the Colombian navy and prominent citizens."

"The procession went to St. Mary's Church, where the requiem mass was held by Father Hogan and Torres was buried with military honors.

"Ships in the Philadelphia harbor held their flags at half-mast.

"An obituary (in the New York Post) named him 'the Franklin of South America'

"Duane and Meade were the executors of his estate", the main asset being the "house he has purchased in Hamiltonville, in West Philly," where he died.

However, if you discover Ambassador Manuel Torres' name one of these days, you will be easily confused and may be tempted to rush to judgment, and you may even call him an "undocumented"— as he indeed is, in the true and better sense of the word.

Was he Puerto Rican, or Mexican, or Colombian?

¿What else could he be?

He was born in Córdoba, Spain, as U.S. Army General George Meade, who was born in nearby Cadiz.

Spanish, as General Meade— born like him in Spain? (Meade was fro m Cadiz, Torres from Córdoba.)

Manuel Torres Trujillo, as his full name was, lived in Philadelphia since 1796, when he was forced into exile by the Spanish colonial government of what is today the country of Colombia, then called Nueva Granada, and lived among us, here in Philadelphia, until his death, occurred at his West Philadelphia home on July 15th, 1822.

When he chose to flee what is today Colombia, when his liberal mind quickly landed him into trouble with the colonial government (he has become friend with Antonio Nariño, who had "dared" to translate "The Rights of Man" from the French into Spanish), he didn't hesitate to head north directly to Philadelphia, the then-Mecca of liberal thinking and America’s own quest for freedom— free from the autocratic monarchies, who held absolute powers over their colonies.

Chief among them the slave trade from Africa practiced by all European colonial powers as it was one of the best businesses of the century.

Philadelphia, however, was a place where the questioning took place on a daily basis, was actively proposed, and didn't exile anybody.

Ambassador Manuel Torres was one of these intellectuals with social skills who quickly made friends in a city where political freedoms and religious liberty had been conquered in a bloody war against the most powerful army in the world.

200 years later, however, no one has the slightest idea of who he was.

RELATED CONTENT

No references, for example, in the Union League of Philadelphia Historical Foundation; few of his articles published in Aurora may remain in the Pennsylvania Historical Society.

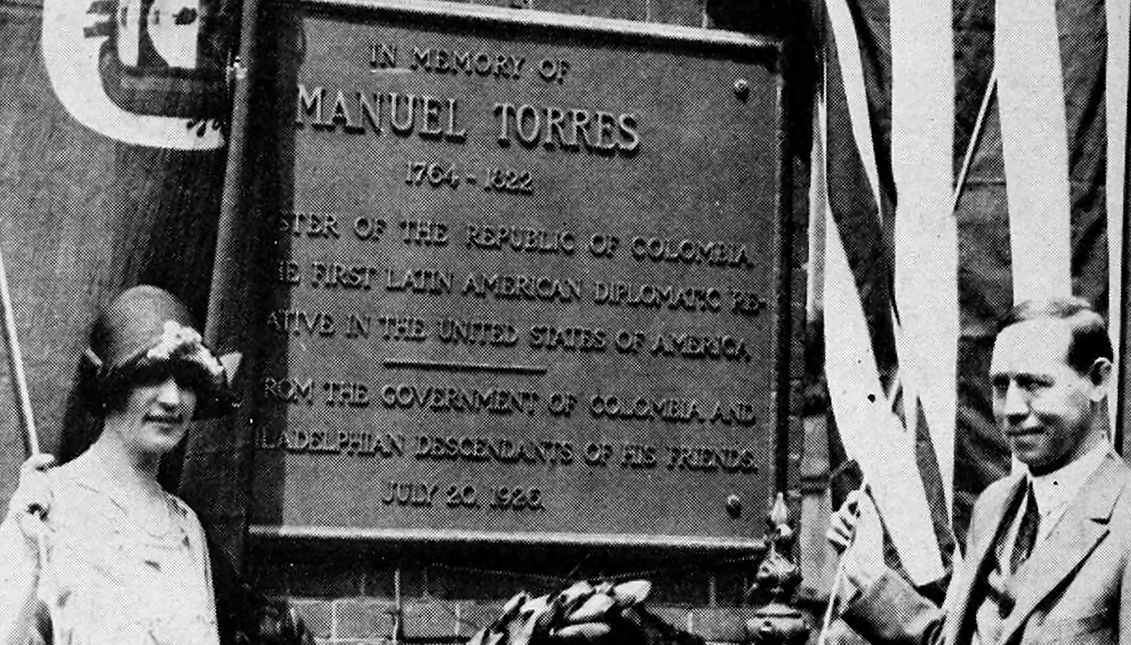

If in 1928 “the descendants of his friends from 100 years earlier” decided to rescue his memory and placed a plaque in front of the St. Mary’s Church, on 2nd Street, where his remains rest in total serenity today, and total anonymity, when the descendants of Torres’ friends are also dead and forgotten.

It was there where I first bumped into his memory, during yet another Sunday afternoon walk full of boredom.

A man of Latino descent whose name is inscribed on a historic wall in the most historic section of this historic city?

Where the American Revolution was conceived?

Where it was written out out by Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, and carried out by General George Washington and his famous Aide-de-Camp Alexander Hamilton, memorialized by Broadway writer and actor Lin Manuel Miranda.

That was what attracted Ambassador Torres to Philadelphia in the first place, a city where he arrived, as Benjamin Franklin did some years earlier, determined to make a name for himself life for himself and lead a life making a decisive contribution to his fellow human beings.

Both accomplished that. The first was likened to the second and was called by an NYC newspaper "The Franklin of South America".

At AL DÍA, we decided to rescue the memory of the most distinguished Philadelphian of Latino descent that has ever lived here in the city — a citizen of the nation, and beyond that, a citizen of the world, and also of the cosmos, as he was not descendant of Spain, but a descendant from 2 consecutive empires that preceded the one built from the Peninsula Ibérica.

AL DÍA will celebrate Manuel Torres in the year 2021, a year in advance of the 200-year anniversary of his passing.

His spirit, as well as his memory, give the celebration of Hispanic Heritage in the U.S. a new and significant meaning.

The “Manuel Torres” Awards will give new meaning to the “AL DÍA Archetypes” of 2021, which are the best reflections of excellence among Americans of Latino descent in the current century in the areas of Health, Education, Science, Law, Armed Forces, Public Service, the Arts, the Entrepreneurial Spirit, Sports, Film, and Entertainment, among others.

AL DÍA does here and now a declaration that we will do anything in our powers and resources to discover, reveal and propagate the personal and public story of the first American of Latino descent in the first capital of the United States of America, born like U.S. Army General George Meade in Spain.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.