Framing Ferguson

MORE IN THIS SECTION

There is nothing — and we mean nothing — that puts U.S. citizens on the defensive more effectively than being told we have taken — or condoned — a morally suspect set of actions. To wit, look at our recalcitrance — collectively — to speak of the humanitarian crisis at the border a refugee crisis rather than an immigration one, even after the nudging of folks from the United Nations’ High Commissioner on Refugees office.

So, what do we do now that Egypt, China, Russia and Iran (countries whose human rights records we’ve carped about for years) are calling us out for a “racial divide (that) still remains a deeply-rooted chronic disease that keeps tearing U.S. society apart, just as manifested by the latest racial riot in Missouri,” as one Chinese commentary put it? Do we write it off as gleeful table-turning?

No. It is a wake-up call for us to take a hard look at the “us vs. them” narrative that at best dismisses the genuine questions, concerns and protests of our nation’s “minority” populations and, at worst, answers those concerns, questions and protests with violence.

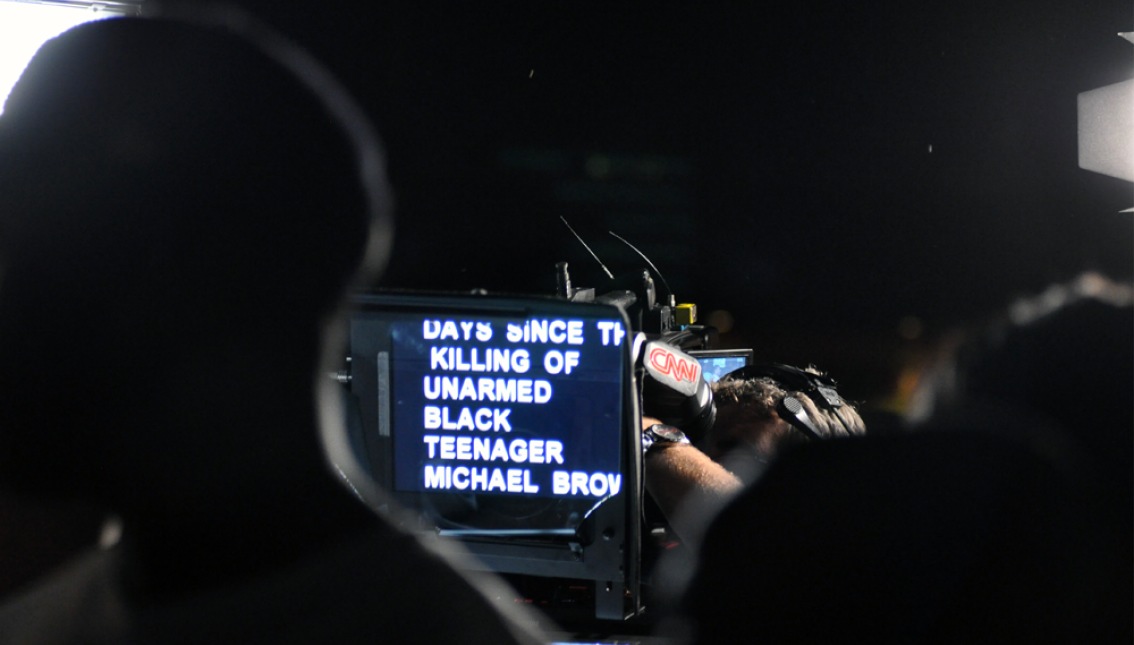

Across the nation, protesters have adopted a “hands up, don’t shoot” posture and chant, to echo the words 18-year-old Michael Brown allegedly called out, and to imitate the posture he reportedly was in when officer Darren Wilson shot him six times. As with the killing of Trayvon Martin, the shooting speaks to the entrenched fear of, and automatic criminalization of, young Black men, especially by law enforcement agents.

The rationalizations and justifications for the fatal shooting have already started. We’ve heard reports that Brown taunted Wilson, or that he hit the officer; we’ve been told he shoplifted a box of cigars, and that he had been smoking marijuana. Even if each of those allegations turns out to true, what sort of derangement is required to believe that they justify the “death penalty” they wrought?

The derangement of a racial profiling so systemic, so entrenched, that it finds purchase well beyond policing.

The media, for example.

The recent AP tweet about verdict in the case of Renisha McBride’s killer, for example, posited the (white) shooter as a suburban homeowner and the (Black, young woman) victim as a drunk person on his porch — thereby according respectability to the perpetrator of violence. Violence that, without putting too fine a point on it, undoubtedly wouldn’t have happened were it not for McBride’s skin color. (Ditto for Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant, and many others.)

About Ferguson, some commentors on social media have noted that the tone of the coverage only changed from “them” (the protestors) to “we” when journalists from the mainstream media started being ill-treated and arrested by police as well.

Meantime, Pew Research Center released a report “Stark Racial Divisions in Reactions to Ferguson Police Shooting,” which indicates that while 80 percent of Black Americans believe Brown’s shooting raises racial issues, only 37 percent of white Americans believe it does. Sixty-five percent of Black Americans believe the police have gone too far in their response, while only 33 percent of white Americans do. Meanwhile, of the Latino sampling in the survey, only 18 percent were interested enough to be following the story.

While there are some flags in terms of the number of Latinos sampled (small, and affording an 11 point plus/minus margin of error), it is still an indicator that, as Aura Bogado of Colorlines said in her piece about it, “Non-black Latinos have a long way to go in confronting our anti-black biases.” If it is true that we’re not adding our voices to those decrying the overzealous policing in Ferguson because of some sense that it is isn’t about “us,” we need to grow up. And step up.

To paraphrase a video commentary writer Solomon Jones did for AL DÍA, we need to unite to demand justice. We need to care about it and be attentive to it. Otherwise, we will surely never experience it.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.