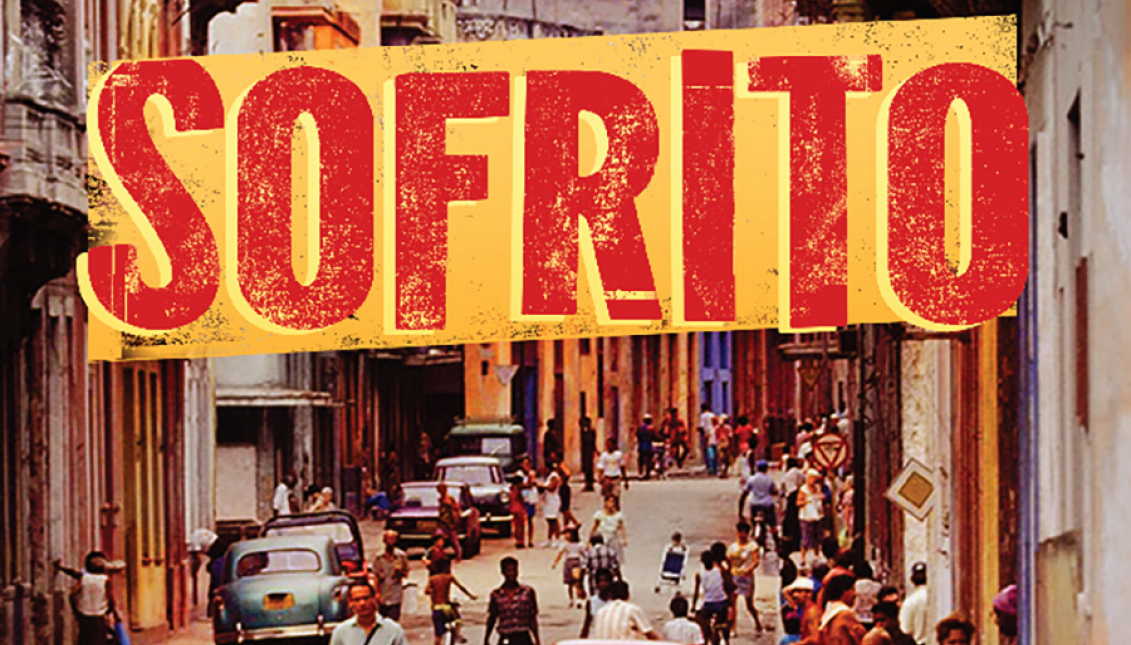

Cinco Puntos Press to release Phillippe Diederich's 'Sofrito' in May

Phillippe Diederich's debut novel, "Sofrito" is part mystery, part foodie road trip.

Phillippe Diederich's debut novel, "Sofrito" is part mystery, part foodie road trip. "Food is the road home—geographically, emotionally, metaphorically" in the novel, says author Cristina García, whose "Dreaming in Cuban" was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1992. Diederich himself, a Haitian American writer and photojournalist whose parents were kicked out of Haiti by Papa Doc in the 1960s and so was raised in Mexico City and Miami, considers it "immigrant fiction, but with a different approach."

The novel's storyline is blend of ingenious and intriguing: "Frank Delgado owns a failing Cuban restaurant in Manhattan's Upper East Side. He decides he'll save the restaurant by traveling to Cuba to steal the legendary chicken recipe from the famed El Ajillo restaurant in Havana. The recipe is a state secret, so prized that no cook knows the whole recipe. But Frank's rationale is ironclad—Fidel stole the secret from his family, so he will steal it back. Frank has no interest in Cuba. His parents fled after the Revolution. His dead father spent his life erasing all traces of Cuba from his heart. So Frank is not prepared for the real Cuba. As he (falls in love and) unwraps the heroic story of his parents' life, Cuba begins to bind Frank together, the way a good sofrito binds the flavors of a Cuban dish."

We caught up with Diederich in advance of the novel's release by Cinco Puntos Press in May.

AL DÍA: What was the prompt for this novel? Do you think it fits within any particular genre?

Diederich: Sofrito came about from multiple directions. I was looking for an idea — something that would work as a story because I’d made two other attempts at writing a novel but failed miserably because they lacked story. I had also been spending a lot of time in Cuba because at the time I was working as a photojournalist based in Miami and Mexico City. I knew I wanted to set the novel in Cuba, but I couldn’t find a vehicle. Why would this man go to Cuba? Then during a trip to Havana I ate at a restaurant and someone mentioned the recipe was a big secret. This gave me the main idea for Sofrito.

As for genre: my publisher calls Sofrito a mystery for foodies. I think that’s a good way to describe it. But I also like to think of the book as part of the genre of immigrant fiction but with a different approach since it’s not about the journey to the U.S. and assimilation into American society or about rising out of poverty. Here are these middle class Cuban-Americans who are disconnected from their heritage. They are more American than Cuban. Does that make it immigrant fiction? Is it the reverse? I’m not really sure. They say write what you’d like to read yourself. That’s what I did.

Tell me about the food, metaphorical and real.

The food. At the time when I wrote the first drafts of Sofrito I was learning how to cook. I had just bought a home. It was the first time I felt a sense of permanence in a very long time. So I was exploring this world of cooking, and I think that’s where the food thing came from for Sofrito. Also, I have always felt that food has its own distinct flavor for the time and a place when you taste a particular dish. And you can never go back to that again. For example, there was a little roadside hamburger stand in the Condesa neighborhood in Mexico City. It was always crowded. The owner must be rich. Anyway, those burgers were something else. But even if I went back there now, they would never taste as good as I remember them. Those burgers are a large part of my nostalgia for my years in Mexico in the 1990s. I think that’s where I was going with how food plays out in Sofrito. The food had to be there. It had to be good, but I couldn’t be to detailed because I didn’t want to kill the magic. That’s why there’s no recipe or detail description of the food. Something had to be left to the imagination.

The other thing was that Maduros, the restaurant in the book, is all about fusion cuisine. When I wrote the first draft of the novel around 2002, it was kind of a novelty. In Sofrito I wanted to play off of the fact that Frank and Pepe and Justo were straying from their Cuban roots and that was something that was leading the restaurant to failure. They needed to get back to basics. They needed to start with a strong Sofrito.

What was your greatest challenge in writing the book? Your greatest triumph?

My greatest challenge in writing the book was to build a story that held all the layers of the story in a way that made sense. I wanted to infuse the book with history and the different opinions about Cuba and the Castro government and capture the true human perspective of how big political changes (like the Cuban revolution and the embargo) influence the average Cuban. I didn’t want to preach or hit anyone over the head with it. But I feel this is a very important part of who we are as citizens of Latin America and the Caribbean. I find myself attracted to what we are experiencing now as the result of decades of cold war politics.

My greatest triumph? I don’t know. I worked on Sofrito for a long time. Getting it published makes me feel as if it’s finally finished. Can that be a triumph?

Have you written other books, other stories?

In the last few years I have written about a dozen short stories all of which deal with life in rural Mexico or with Mexican immigrants in the U.S. You can read some of them online at Burrow Press Review, Acentos Review and Hobart Pulp.

In early 2016 Cinco Puntos will be publishing my young adult novel “Playing with the Devil’s Fire” which follows a 12-year old boy whose parents disappear after Narcos move into the small town where he lives.

Are there common concerns underpinning all your stories?

I think I write about the disconnect between people and/or family; about the influence the cold war left in Latin America, and to tell the story of people we don’t often hear about. I also try to show that what many in the U.S. see as an issue that is presented by the media as black and white is really made up of multiple layers of gray: immigration, exile, politics, individual economics, love. I think these issues are very complex and really depend on the individual. Sofrito has that, and my Mexican short stories have that. And then there is that John Steinbeck influence.

Do you think there is a Haitian-American literary style? Do you see yourself as an easy fit within it?

As far as Haitian literary work, I have only read Edwidge Danticat’s work and recently “God Loves Haiti” by Dimitri Elias Léger as well as one of Haiti’s oldest novels, Stella. I think I identify more with writers who have no ‘home’. I think my identity is more in line with people who are multi-cultural or split between homes and citizenship. I am not American, I am not 100 percent Haitian. I have no real Mexican in me, but I love Mexico and I feel Mexican because it’s the country I grew up in. And then there is Cuba. Another country I love, but I’m not Cuban. Maybe I write what I write to find my way in this mess.

Do you write in any languages other than English?

I write in English with a bit of Spanish. But I think my English is stylistically affected by my Spanish so that sometimes my sentence structure or my sayings are a little off as far as being wholly American. But I think it’s more of a cultural than a linguistic influence.

I find myself having literary conversations with waiters, taxi drivers and young people in the street in countries like Mexico and Guatemala and Cuba. If Latinos are not reading as much in the U.S. it’s because the books that are of interest to Latinos are not being published by U.S. publishers.

We hear the stereotype that Latinos are neither readers nor writers. Do you think there is any truth to that?

I think that stereotype is as wrong as the one that Latinos are poor and work only as gardeners and maids. The bookfair in Guadalajara, Mexico has become one of the largest book fairs in the continent. Latin American countries all have very strong literary traditions. I find myself having literary conversations with waiters, taxi drivers and young people in the street in countries like Mexico and Guatemala and Cuba. If Latinos are not reading as much in the U.S. it’s because the books that are of interest to Latinos are not being published by U.S. publishers. Regrettably, publishing in this country is a ‘white’ business. Someone can write yet another book about an upper middle class white person coming to NYC and get a six figure advance. But if you write about anything outside that bubble, if you write about the struggles of people on the U.S. Mexico border or about the drama of a middle class Latin American family in Orlando, Florida — good luck.

To give you an example: when I was sending out my novel “Playing with the Devil’s Fire” I received a comment from a very reputable agent. They had a problem with the novel because they couldn’t understand why the boy didn’t just call 911 to get help. I was shocked. Call 911 in rural Mexico? Last year 43 students disappeared at the hands of the police. Over 60 thousand people have been killed or disappeared because of Narco violence. The politicians and the police as a corrupt as they come, and everyone in Mexico knows this. Call 911? Sh**.

How important do you think it is to see ourselves represented as characters in books? To see ourselves represented as writers on library shelves and bookstore displays?

I think this is very important. In the early-90s when I was trying to write, I was lost. I had never really lived the experience of growing up in the suburbs of the U.S. or a small town or anything like that. At the time I was reading a lot of Southern writers and I loved them all, but I couldn’t understand what I could write about. My experience was so different from everything I read. Then I read Sandra Cisneros and everything changed. In “The House on Mango Street,” she dealt with the duality of worlds that I grew up with, going back to Mexico to see family. I was going to Haiti to see family. I belonged to both worlds but I also did not belong to both worlds. And then there was Mexico, where I grew up. So her book showed me that I could write about my own experience. Around that time I also read Cristina Garcia’s “Dreaming in Cuban” and Francisco Goldman’s “The Long Night of White Chickens.” As I discovered these books, I realized my own story, or whatever I wanted to write about was not only worth it, but had the potential for a strong and important story. It was as if the floodgates opened.

I think we all like to read books we can identify with. And as much as it should be about seeing ourselves in the books, it’s also about understanding the perspective of the characters in these books. I think Sherman Alexie, for example, does a tremendous job with this. It’s not in just that Native Americans can see themselves in his books, but it’s how all of us can see how Native Americans see the world.

Do you come from a family of readers? A family of writers?

My parents are readers. And my father was a journalist and is the author of non-fiction books. I grew up with politics. They were kicked out of Haiti in 1963, so exile and politics are a big deal. Strangely, I didn’t really get into reading until I was in 10th grade when we read Russian short stories in class. I was hooked after that.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.