Reproductive justice: 20 years of activism, but still not a debate topic?

If you’ve been watching the various 2016 presidential debates and forums, you’ve heard a handful of questions on reproductive rights. Candidates have voiced…

If you’ve been watching the various 2016 presidential debates and forums, you’ve heard a handful of questions on reproductive rights. Candidates have voiced their (mostly well-known) positions on abortion and contraception. Bernie Sanders even spoke frankly about science and sex education.

But what you haven’t heard is a debate question about reproductive justice. And the difference is important. Reproductive rights don’t stop with abortion and contraception. A true vision of reproductive justice stretches far beyond that, as this history recounts:

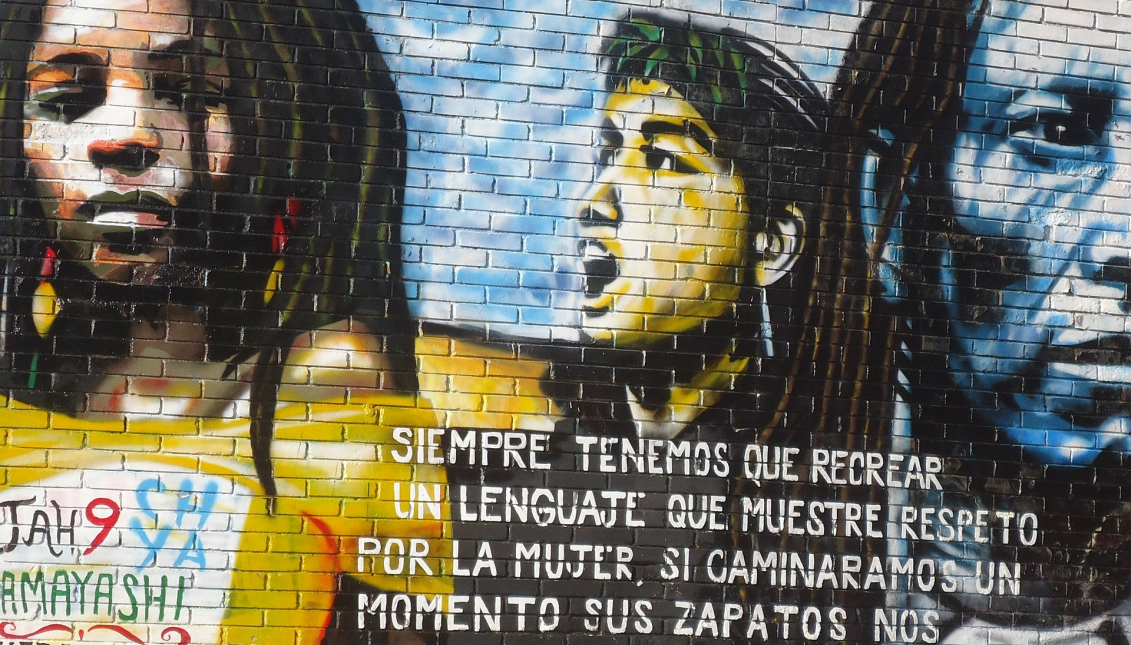

In 1994, a room full of women of color worked on naming the specific injustices we all face on a daily basis, focusing specifically on creating a framework that would move us beyond the traditional pro-choice narrative and into the reality of our lived experiences as a rich, nuanced, and intersectional community.

The term that emerged from their discussion was reproductive justice. In the two decades since, the phrase has been broadly adopted by Latina, African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Native activists and communities. Yet neither the term itself, nor – crucially – the values it represents have been fully embraced by the predominantly white organizations whose spokespeople often dominate media coverage of reproductive issues.

Indeed, as recently as 2014, advocates of color wrote an open letter to Planned Parenthood, expressing their disappointment and frustration with the erasure of their work by reproductive-rights advocates in comments to the news media.

Though their letter triggered a quick, seemingly responsive reply from Planned Parenthood, the incident was a vivid illustration of the blind spots – accidental or otherwise – that persist in powerful institutions.

Those blind spots persist even as women of color now comprise more than 1 in 3 American women overall, and more than 40% of Millennials. Earlier this month, candidate Hillary Clinton was asked whether she thought young women were “complacent” about reproductive rights. “I don’t have any overall data or information to respond to that,” she said.

It was a remarkable admission given the steady outpouring of conversation and commentary among women of color on issues of reproductive justice. From Twitter hashtags to op-ed pieces, the conversation is passionate and free-flowing, publicly available for all to access. Whether analyzing lead-poisoning in Flint or police brutality, women of color routinely connect the dots on issues of reproductive justice, often explicitly spelling out their fears and articulating their visions for a better world.

Notably, it is also a conversation that white reproductive-rights activists are being explicitly invited to join. Writing in the The Nation, Dani McClain had this to say:

[T]he killing of Michael Brown, like the killing of many young black people before him, is rarely framed as a feminist issue or as an issue of pressing importance to those who advocate for choice, self-determination and dignity as they relate to family life. With this most recent killing, I am wondering what it would take for more people in feminist and reproductive rights circles to begin to think of parents such as Lesley McSpadden […] as women they advocate for just as passionately and vigorously as they advocate for a young woman’s right to contraception or an overwhelmed mother of three’s right to an abortion.

Yet Clinton’s answer did not address these issues, instead staying strictly in the lane of reproductive rights. Nor did the moderator who asked her the question follow up.

It’s tempting to imagine that having more debates moderated by women of color could help with this problem. Of course, it shouldn’t require a woman of color to ask the question, but it’s understandable why some might pin their hopes on that goal. Debate moderators, and the questions they ask, are essentially a matter of public record – and unfortunately, white moderators have a spotty record in posing questions about issues facing women of color.

So it might seem that a black female moderator could fare better in getting a relevant issue on the table. And indeed, back in 2004, vice presidential debate moderator Gwen Ifill asked candidates Dick Cheney and John Edwards about the issue of HIV among African-American women.

Despite the fact that the question was asked by Ifill — an African-American woman herself — both candidates focused most of their answers on HIV/AIDS in Africa. As in the continent. It was a disappointing moment that seemed to once again erase the concerns of black American women.

Twelve years later, Ifill will have another chance to put a question about issues facing women of color on the table. She’ll be co-moderating the final Democratic debate later this spring. With luck, she may ask about reproductive justice.

But it shouldn’t be up to her alone. If we think it is, we’re creating our own blind spot – one that we’ve already had two decades to overcome.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.