Teaching Quechua: Beyond the Classroom, Beyond Language

Professor Amėrico Mendoza-Mori designed and began the Quechua Language and Andean Culture program for The University in Pennsylvania in 2014, and since then,…

After you read the following word, close your eyes for a few minutes:

Quechua.

Now, what images were just projected into your mind’s stage? Was the backdrop made up of lush Amazonian rainforests, dripping speckled hues of fuchsia, yellow, and indigo amidst the flutters of macaws and the sighs of jaguars lazing in canopies? Or, was your stage’s setting covered in the majestic stone ruins of the Incan and Andean empires, the skyward dominators of Peruvian mountains, strung together by grass-rope bridges? Who were the actors and actresses in your vision of the word Quechua? Were they clad in a rainbow of tough alpaca wool, in lavish venerations for the temperamental deities Inti, Illapa, and Pachamama?

Was this setting, this cast, this script, stuck and immortalized in antiquity? Were these ghosts of South America’s romanticized past?

Odds are that you, upon closing your eyes and sparking connections between the language and the culture of Quechua, did not materialize imagery of 2017, of cars bustling and beeping through a metropolitan Cusco, of the indigenous thriving in modernity. And, you certainly did not consider a background painted in the likeness of the hallowed halls of The University of Pennsylvania or of Florida International University, as a location in which Quechua could be recognized.

Our inability to correlate the language, lifestyles, and customs of the indigenous- both in The United States and in Central and South America -is primarily due to our mainstream media’s and curriculum’s inattentiveness to (or abject disregard for) a people that we exoticize as being of the past, as existing only in the liminal space between “dead culture” and voyeuristic tourist attraction.

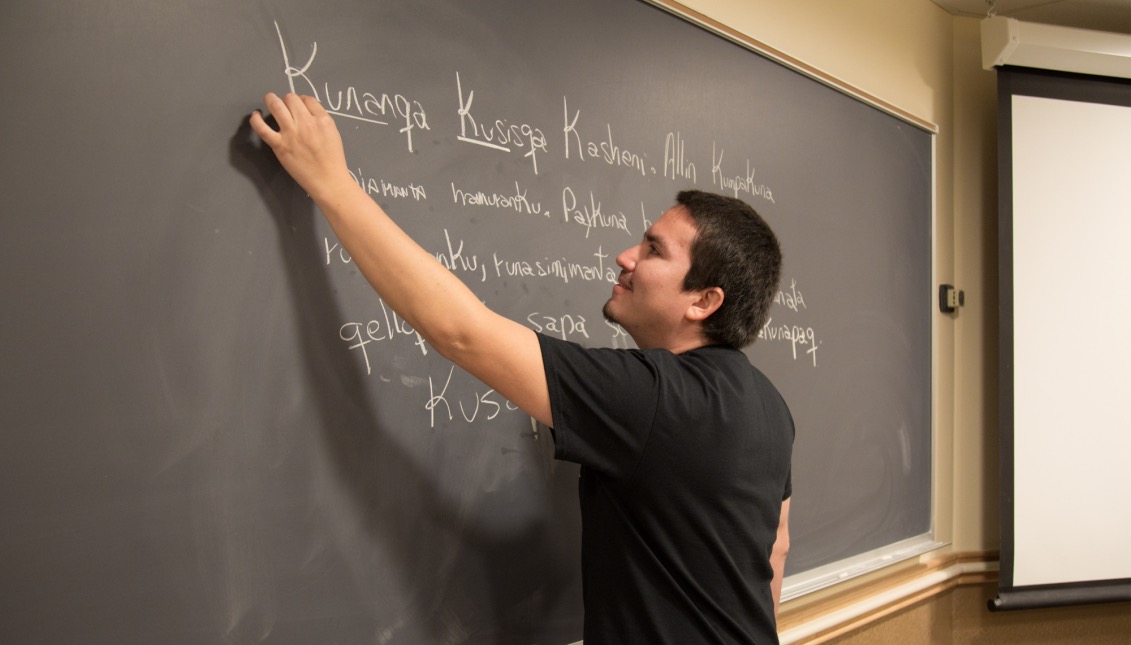

Professor Américo Mendoza-Mori of Penn’s Quechua Language and Andean Culture Program is committed to- aside from teaching beginner and intermediate levels of Quechua and Spanish to Ivy League millennials -dispelling the myths of the “imaginary” indigenous, and giving visibility to a heritage that more than eight million people claim in South America, and that hundreds speak and are descended from in Spain, Italy, and The United States.

Although the ethnic background of most of his students are US Latino, another minority, or simply curious White Americans who see the value in Latin American and Native American studies without necessarily claiming a cultural foundation in either, Américo was born in the coast of Peru. His mother was born in an Amazonian city, while his father was from a rural village at the foot of a valley in the Andes, two places were Quechua is spoken. However, neither his mother nor his father knew how to speak Quechua (nor did they want to). Américo cannot recall hearing his grandparents speak Quechua to each other and to their neighbors and older relatives during visits in his childhood because it was so devalued (although he did find out later that his grandma spoke the language). The professor hardly remembers any of his ethnic background in Quechua sparking an interest or a potent impulse to learn the language until much later when he felt called to reclaim his linguistic roots as an undergraduate student in Lima and as a doctoral student in Miami, Florida.

The reason for being a late-bloomer? Stigma:

“Some statistics suggest that 60% of the people in Cusco speak Quechua, but people don’t necessarily want to speak the language. My parents gave into the reputation that Quechua holds too. That stigma is unfortunate. There’s been a legacy, a colonial legacy… And Peru has created social hierarchies that disadvantage those who are indigenous or live certain lifestyles, have certain physical features, wear certain clothing, or speak a certain language. Quechua has been an aspect to discrimination. So, for me, my Quechua roots were always on the backburner because, unfortunately, it lacked social prestige. I never really thought much about that aspect of my identity, even though it was always there, and even permeated in the Spanish that I spoke.”

After recent events in Charlottesville, Virginia, Américo believes that it is now more important than ever to redefine our notion of the American narrative, and of American identity. This concept of “identity” was what Américo was initially fascinated by, both while receiving his Bachelor's at La Universidad Nacional de San Marcos, and later while living in West Kendall and working at a laundromat while taking graduate courses at The University of Miami. He was intrigued by the ways that we- especially Americans -imagine nationhood, ethnicity, and race, and how sometimes our narrow signifiers and definitions can be “risky” because we can ignore the vast spectrum of what makes us who we are. “It’s normal, we’re humans, and we want a simplified idea… But after Charlottesville, you can see the danger in simplification, in ‘othering’, because it can lead to misunderstanding, hatred, and discrimination,” Américo asserts.

“People are more aware now that we do not need to give-up who we are or where we come from in order to join the idealized American narrative. These people want to bring their own unique something to build-up a more diverse and enriched narrative," Américo Mendoza-Mori

So, while thinking about identities and, inevitably in his own, Américo began to center and focus his academic research on Andean culture and on Quechua. He spent time living in Cusco, which was his opportunity to begin mastering the language while simultaneously studying its historical, sociopolitical, and cultural context.

Américo’s passionate championing of indigenous cultural awareness, the celebration of linguistic diversity, and the need to bring visibility and value to indigenous persons in academia and beyond has been recognized by local and national media, The United Nations, academic and community-based organizations in Peru and Bolivia, and by Quechua media outlets such as “Ñuqanchik”.

RELATED CONTENT

The Quechua Language and Andean Culture Program at The University of Pennsylvania strives to have a reach that goes beyond the classroom, and includes the well-attended and popular Quechua Student Alliance and Faculty Meeting, open to all, for as Américo contends: “the first level of belongingness [to this group] isn’t even knowledge of the language, it’s acknowledging the value and showing appreciation. We get many minority students and faculty members that show up, for example, because people want to share that commonality of facing the challenge of being different, of being in a place that sometimes does not embrace diversity.”

Nevertheless, it’s easy to study a culture or a language in the academic “bubble”, and never even travel or interact with the places where these cultures and languages are dominant. Knowledge constitutes more than just research and courses, it is created and built-upon by connection, by field work, by mission trips, and by events such as film screenings or music concerts. This exchange of information and experience brings students from Penn to research pro-seminars in Cusco, but it also facilitates and allots time to community-based leaders from Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador to come to The University of Pennsylvania to give lectures and incite the discourse that is integral to indigenous visibility and education. Oftentimes, Américo relays, “most people at Penn and in academia in general are surprised when people from more rural, less developed, or native reservations and regions come to speak. They are used to seeing these people as a group that we study, not a group that we are meant to learn from.”

The main ambition of The Quechua Language and Andean Culture Program is to create spaces of encounter, an encounter of identities that are broadened, rewritten, claimed, reappropriated, and finally, deemed worthy of recognition.

In every passing moment of our lives, we are either unconsciously or consciously trying to make sense of one question: Who am I? An intrinsic part of our identities is the language that we speak, the language that we emote in, express and create in, sing loudly in, and even dream in. For Américo, the connection between himself and Quechua was an obvious link, but for some US Latinos, that link may not be as strong as, say, with Nahuatl or even Spanish. Many US Latinos, usually second or third generation, do not know how to speak Spanish- and, much less an indigenous language or dialect from where they originate. That lack tends to come from this stigma of retaining your home language. Latinos felt that they had to give that up to “join the masses”, that speaking English was integral to what it “meant” to be an American. Many of these US Latinos are interested in going back to their linguistic roots and creating a new narrative for themselves, but they may have that barrier of language or may feel intimidated by learning the languages and dialects from their homeland.

Part of the Quechua program, in a wider sense, is to get people to re-think about what it means to be an American through celebrating and encouraging minority cultures and languages of the Americas:

“People are more aware now that we do not need to give-up who we are or where we come from in order to join the idealized American narrative. These people want to bring their own unique something to build-up a more diverse and enriched narrative. I think that’s the key point. People are more aware now that, in order to build a better society, we need to reclaim who we are and bring forth diversity. You’re not just learning words when you learn a language, and you’re not just learning about people when you take East Asian, Native American, or African Studies. You are getting a life skill in understanding other cultures, and that is a priceless asset,” Américo muses.

Latinos felt that they had to give that up to “join the masses”, that speaking English was integral to what it “meant” to be an American.

In the United States, we have a legacy of ignoring our immigrant multiculturalism and our indigenous roots in order to fabricate an imaginary, oversimplified and whitewashed identity that we are encouraged to conform to. This restraining and limiting definition of who we are as a country has perpetuated, not only intolerance and ignorance, but also a disconnect between minority groups and Native Americans, which has hindered opportunities for cross cultural exchange of knowledge and belief.

How will you rewrite your American narrative, and what languages will you write it in? This is the lesson that Professor Américo Mendoza-Mori hopefully intends to impart in class, a lesson that can spread beyond Locust Walk and into the consciousness of all in The Americas.

LEAVE A COMMENT: